I’m a big fan of jazz arrangers who did the charts for scores of famous singers and big bands. Names like Billy May, Gordon Jenkins, Marty Paich and Neal Hefti (who did about 50% of Count Basie’s charts) come to mind. The most famous of all was arguably Nelson Riddle. We will likely not see the likes this kind of talent cluster for a long time, if ever, especially since this is not a popular music format these days. Sinatra worked with all of them, but said that Riddle was his favorite because he had the “best bag of tricks” of all of them.

This is an excellent article on Riddle by Terry Teachout, one of our greatest music and theater critics who writes primarily in the WSJ and Commentary Magazine. This is from this month’s Commentary Magazine.

The Man Who (Re)made Sinatra

The Riddle of Nelson

by Terry Teachout

Nelson Riddle, who was born 100 years ago, is the only one of the song arrangers of the postwar era who is still widely known by name—and that is because of a fluke. In 1983, he recorded the first of three albums on which Linda Ronstadt sang standards backed by his arrangements, and he received credit on the album covers for his participation. Riddle, who had been shunted into semi-obscurity by the rise of rock, found himself suddenly famous. Ronstadt’s albums sold 7 million copies and introduced him to a new generation of listeners.

What do arrangers do? When working with pop singers, they take songs originally written and published for voice and piano and turn their piano parts into full-blown orchestral scores, adding instrumental introductions, new underscoring, and (sometimes) interludes of their own devising, all of which may or may not be derived from the original song’s melody and harmonies. Few arrangers write their own songs, just as it is extremely unusual for songwriters to make their own arrangements, or even to approve an arrangement by someone else: Both are specialists, and the skill sets involved are very different.

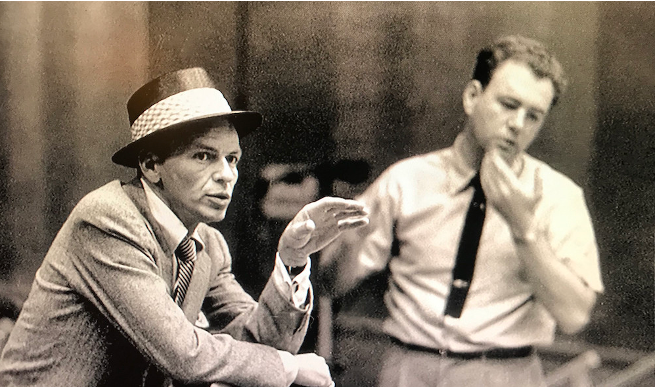

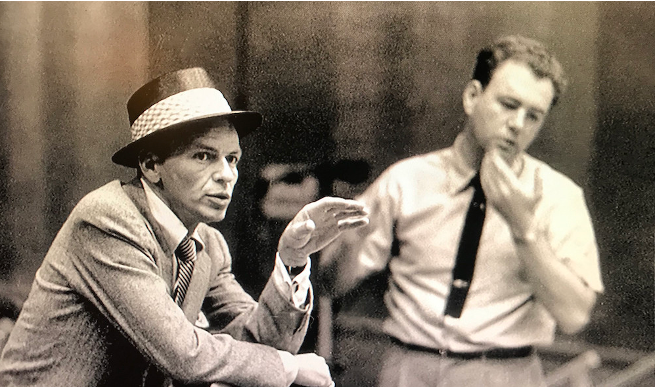

Riddle was, perhaps, the greatest of all the arrangers who worked on the Great American Songbook, primarily because of the work he did in the 1950s with Frank Sinatra. The two men were brought together by Capitol Records in 1953 in the hope of updating Sinatra’s singing style, which still recalled his youthful crooning of sentimental ballads. Within a matter of years, Sinatra had recorded his two finest albums, Songs for Swingin’ Lovers! (1956) and Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely (1958), on which he emerged decisively as a mature artist, in part because of Riddle’s sympathetic backing. Riddle also wrote arrangements of like quality for Rosemary Clooney, Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Judy Garland, Antônio Carlos Jobim, Peggy Lee, and Dean Martin. Riddle’s innovative work defined the predominant postwar style of arranging, which may be the defining sound of the American century. Such an artistic force is deserving of a first-class full-length biography. Alas, Peter Levinson’s September in the Rain (2001), though full of illuminating detail about his life, is musically uninformed, while Geoffrey Littlefield’s newly published Nelson Riddle: Music with a Heartbeat, nominally co-written with Riddle’s son Christopher, is a vanity-press disaster, besmirched by factual errors and even more musically ignorant than Levinson’s book.1 Still, September in the Rain does let us see how Riddle developed as an artist, in the process enriching our understanding of the life of the chronically melancholy man and his uncomfortable relationship with the greatest popular singer of the 20th century.

BORN IN New Jersey, Riddle became obsessed with music as a boy. While early encounters with Ravel’s Boléro and Debussy’s “Reflets dans l’eau” gave him a lasting passion for the complex harmonies of the French impressionists, he decided that he wanted instead to write for the big bands of the day. He studied with Bill Finegan, a classically trained composer-arranger who had worked with Glenn Miller. And after serving in World War II, Riddle moved to Los Angeles and set up shop. He took instruction from the classical composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, whose other pupils included future movie-music giants Jerry Goldsmith, Henry Mancini, and John Williams. In 1950, Riddle wrote the string chart for Nat King Cole’s “Mona Lisa,” and the record’s success not only launched a lasting musical partnership, but also led to Riddle’s becoming music director de facto for Capitol.

Shortly afterward, Riddle met Sinatra, whose singing career was on the rocks when Capitol signed him in 1953. Sinatra was musically galvanized by the encounter. The Riddle style, which was not quite fully formed when he arranged “Mona Lisa,” had by then matured into one of the most recognizable sounds of the ’50s (so much so that Billy May, one of Sinatra’s other arrangers, parodied it in a clever 1959 musical spoof called “Solving the Riddle”). It was ideally suited to the purpose of making Sinatra known to listeners too young to have known him as the skinny balladeer of the ’40s on whom their mothers had doted, and the two men started working together regularly at once.

Prior to writing an arrangement for Sinatra, Riddle would consult closely with the singer on its overall shape. Then he started writing, following a three-step formula that he described in an interview: “First, find the peak of the song and build the whole arrangement to that peak, pacing itself as [Sinatra] paces himself vocally. Second, when he’s moving, get the hell out of the way. When he’s doing nothing, move in fast and establish something…build about two-thirds of the way through, and then fade to a surprise ending.”

These steps can all be heard in the version of Cole Porter’s “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” on Songs for Swingin’ Lovers! It is played by a 34-piece studio orchestra larger than and significantly different in instrumentation from the 16-piece big bands of the Swing Era. Not only do all five saxophonists double on flute or clarinet, but the seven-man brass section is augmented by a bass trombone, one of Riddle’s favorite instruments, and there is also a small string section (three violins, two violas, and three cellos).

Riddle kicks off the song with an unexpectedly asymmetrical six-bar introduction (four- and eight-bar intros are more common) in which clarinets, flutes, and muted trombones toss riffs back and forth, with off-beat chordal punctuation played on a celesta, the keyboard instrument whose bell-like tones Tchaikovsky first popularized in The Nutcracker.

Sinatra enters discreetly and sings a chorus partly accompanied by a soft “bed” of sustained string chords—a touch specifically requested by the singer—and a springy two-beat bass line, with Riddle “getting the hell out of the way” by changing instrumental colors and background patterns from one phrase to the next without diverting attention from the vocal. At no time, not even in the introduction, does he use Porter’s melody in anything other than fragmented form. He leaves it to Sinatra, making the vocal stand out in even higher relief.

At chorus’s end, the rhythm section shifts into straight-ahead four-four time for a 12-bar crescendo for trombones and strings that explodes into a thrillingly fiery trombone solo. Riddle then lowers the volume and Sinatra returns to sing another half-chorus, quickly screwing the tension back up and reaching the song’s climax (and the highest note in his vocal) as he sings, “But each time I do / Just the thought of you / Makes me stop just before I give in.” Once he does so, the volume drops again and the introductory riffs return as Sinatra sings the coda, followed by a surprise ending, a bitonal, Ravel-flavored chord for strings, celesta, and harp that hangs in the air for a breathless instant, then evaporates into silence.

Even when working with a much larger orchestra of near-symphonic proportions, as he did on Only the Lonely, Riddle scored torch songs with the same airy transparency that he brought to swinging numbers. This lightness of touch, which was his trademark, allowed Sinatra to plumb the depths of despair without spilling over into lugubriousness, and it was no less well suited to the brighter singing of Nat Cole and Ella Fitzgerald. With them as with Sinatra, Riddle was the nonpareil collaborator.

This is an excellent article on Riddle by Terry Teachout, one of our greatest music and theater critics who writes primarily in the WSJ and Commentary Magazine. This is from this month’s Commentary Magazine.

The Man Who (Re)made Sinatra

The Riddle of Nelson

by Terry Teachout

Nelson Riddle, who was born 100 years ago, is the only one of the song arrangers of the postwar era who is still widely known by name—and that is because of a fluke. In 1983, he recorded the first of three albums on which Linda Ronstadt sang standards backed by his arrangements, and he received credit on the album covers for his participation. Riddle, who had been shunted into semi-obscurity by the rise of rock, found himself suddenly famous. Ronstadt’s albums sold 7 million copies and introduced him to a new generation of listeners.

What do arrangers do? When working with pop singers, they take songs originally written and published for voice and piano and turn their piano parts into full-blown orchestral scores, adding instrumental introductions, new underscoring, and (sometimes) interludes of their own devising, all of which may or may not be derived from the original song’s melody and harmonies. Few arrangers write their own songs, just as it is extremely unusual for songwriters to make their own arrangements, or even to approve an arrangement by someone else: Both are specialists, and the skill sets involved are very different.

Riddle was, perhaps, the greatest of all the arrangers who worked on the Great American Songbook, primarily because of the work he did in the 1950s with Frank Sinatra. The two men were brought together by Capitol Records in 1953 in the hope of updating Sinatra’s singing style, which still recalled his youthful crooning of sentimental ballads. Within a matter of years, Sinatra had recorded his two finest albums, Songs for Swingin’ Lovers! (1956) and Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely (1958), on which he emerged decisively as a mature artist, in part because of Riddle’s sympathetic backing. Riddle also wrote arrangements of like quality for Rosemary Clooney, Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Judy Garland, Antônio Carlos Jobim, Peggy Lee, and Dean Martin. Riddle’s innovative work defined the predominant postwar style of arranging, which may be the defining sound of the American century. Such an artistic force is deserving of a first-class full-length biography. Alas, Peter Levinson’s September in the Rain (2001), though full of illuminating detail about his life, is musically uninformed, while Geoffrey Littlefield’s newly published Nelson Riddle: Music with a Heartbeat, nominally co-written with Riddle’s son Christopher, is a vanity-press disaster, besmirched by factual errors and even more musically ignorant than Levinson’s book.1 Still, September in the Rain does let us see how Riddle developed as an artist, in the process enriching our understanding of the life of the chronically melancholy man and his uncomfortable relationship with the greatest popular singer of the 20th century.

_____________

BORN IN New Jersey, Riddle became obsessed with music as a boy. While early encounters with Ravel’s Boléro and Debussy’s “Reflets dans l’eau” gave him a lasting passion for the complex harmonies of the French impressionists, he decided that he wanted instead to write for the big bands of the day. He studied with Bill Finegan, a classically trained composer-arranger who had worked with Glenn Miller. And after serving in World War II, Riddle moved to Los Angeles and set up shop. He took instruction from the classical composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, whose other pupils included future movie-music giants Jerry Goldsmith, Henry Mancini, and John Williams. In 1950, Riddle wrote the string chart for Nat King Cole’s “Mona Lisa,” and the record’s success not only launched a lasting musical partnership, but also led to Riddle’s becoming music director de facto for Capitol.

Shortly afterward, Riddle met Sinatra, whose singing career was on the rocks when Capitol signed him in 1953. Sinatra was musically galvanized by the encounter. The Riddle style, which was not quite fully formed when he arranged “Mona Lisa,” had by then matured into one of the most recognizable sounds of the ’50s (so much so that Billy May, one of Sinatra’s other arrangers, parodied it in a clever 1959 musical spoof called “Solving the Riddle”). It was ideally suited to the purpose of making Sinatra known to listeners too young to have known him as the skinny balladeer of the ’40s on whom their mothers had doted, and the two men started working together regularly at once.

Prior to writing an arrangement for Sinatra, Riddle would consult closely with the singer on its overall shape. Then he started writing, following a three-step formula that he described in an interview: “First, find the peak of the song and build the whole arrangement to that peak, pacing itself as [Sinatra] paces himself vocally. Second, when he’s moving, get the hell out of the way. When he’s doing nothing, move in fast and establish something…build about two-thirds of the way through, and then fade to a surprise ending.”

These steps can all be heard in the version of Cole Porter’s “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” on Songs for Swingin’ Lovers! It is played by a 34-piece studio orchestra larger than and significantly different in instrumentation from the 16-piece big bands of the Swing Era. Not only do all five saxophonists double on flute or clarinet, but the seven-man brass section is augmented by a bass trombone, one of Riddle’s favorite instruments, and there is also a small string section (three violins, two violas, and three cellos).

Riddle kicks off the song with an unexpectedly asymmetrical six-bar introduction (four- and eight-bar intros are more common) in which clarinets, flutes, and muted trombones toss riffs back and forth, with off-beat chordal punctuation played on a celesta, the keyboard instrument whose bell-like tones Tchaikovsky first popularized in The Nutcracker.

Sinatra enters discreetly and sings a chorus partly accompanied by a soft “bed” of sustained string chords—a touch specifically requested by the singer—and a springy two-beat bass line, with Riddle “getting the hell out of the way” by changing instrumental colors and background patterns from one phrase to the next without diverting attention from the vocal. At no time, not even in the introduction, does he use Porter’s melody in anything other than fragmented form. He leaves it to Sinatra, making the vocal stand out in even higher relief.

At chorus’s end, the rhythm section shifts into straight-ahead four-four time for a 12-bar crescendo for trombones and strings that explodes into a thrillingly fiery trombone solo. Riddle then lowers the volume and Sinatra returns to sing another half-chorus, quickly screwing the tension back up and reaching the song’s climax (and the highest note in his vocal) as he sings, “But each time I do / Just the thought of you / Makes me stop just before I give in.” Once he does so, the volume drops again and the introductory riffs return as Sinatra sings the coda, followed by a surprise ending, a bitonal, Ravel-flavored chord for strings, celesta, and harp that hangs in the air for a breathless instant, then evaporates into silence.

Even when working with a much larger orchestra of near-symphonic proportions, as he did on Only the Lonely, Riddle scored torch songs with the same airy transparency that he brought to swinging numbers. This lightness of touch, which was his trademark, allowed Sinatra to plumb the depths of despair without spilling over into lugubriousness, and it was no less well suited to the brighter singing of Nat Cole and Ella Fitzgerald. With them as with Sinatra, Riddle was the nonpareil collaborator.