The excitement around the driver grew. It felt like everyone who experienced them was immediately captivated, and soon after the first pairs were finished I committed to do a speaking engagement, to share my process and the work.

It'd be nice to say that the next thing that happened in this long chronicle was that I brought the same patience, discipline and confidence that went into the driver into the cabinetry as well, and greatness was the inevitable outcome. But what really happened was quite different.

A few of the design concerns that needed to be addressed in the cabinetry were these:

Whatever you do, I thought, don't look at the whole elephant. Just keep your head down, and continue to eat. One little forkful at a time.

A ported design was to be my first, and any outcome that required a subwoofer would be judged a failure. This was full-range, or bust. Right from the outset however, modeling the cabinet made clear that regardless of architecture, bass performance was going to be a challenge. In a ported enclosure that's of course dependent upon box volume and tuning frequency. However, the Thiele Small parameters of the driver are also critically important. A few key values are Fs (the resonant frequency of the driver in free-air), Qts (derived from the electrical and mechanical quality of the driver), and Vas (the volume of air in a cubic meter with equivalent compliance as the driver suspension).

Unsurprisingly, modeling showed that large volumes tuned properly played deep. However, beyond a certain scale enclosures became edifices, too unappealing and imposing. I decided that 120 liters would be my limit, and anything further would need to be achieved by way of "apparent" internal volume.

Low Qts predicted a smooth roll-off, but well above my target in the mid to low 30's. High Qts played significantly deeper, but left a +3dB boost in output just before roll-off, for which impractically lower tuning seemed the only remedy. The otherwise wonderful ultra-soft driver suspension came with ultra-high Vas, which unfortunately predicted a more pronounced hump, and an earlier, steeper roll-off. Every choice it seemed, was a maddening trade-off. The trick was clearly in performing a balancing act between them all.

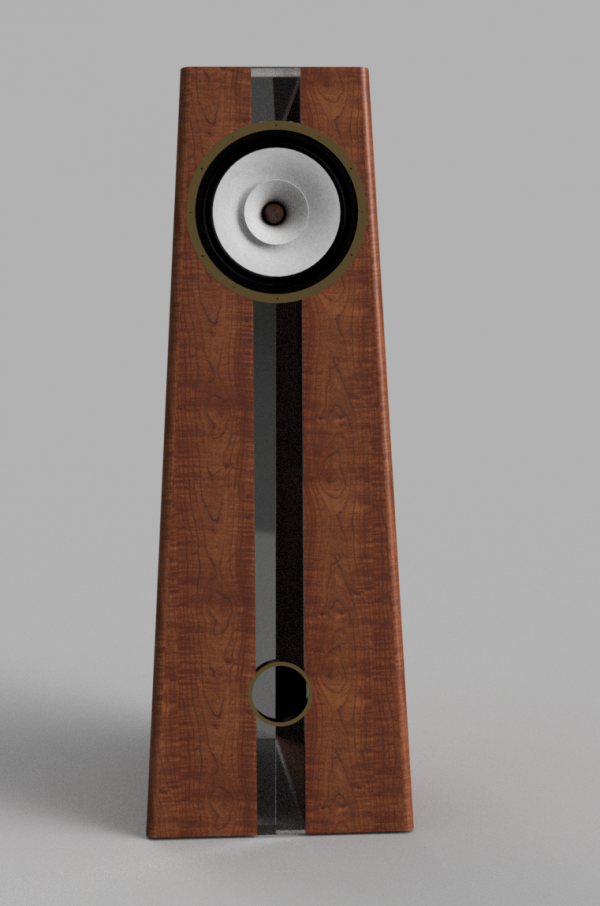

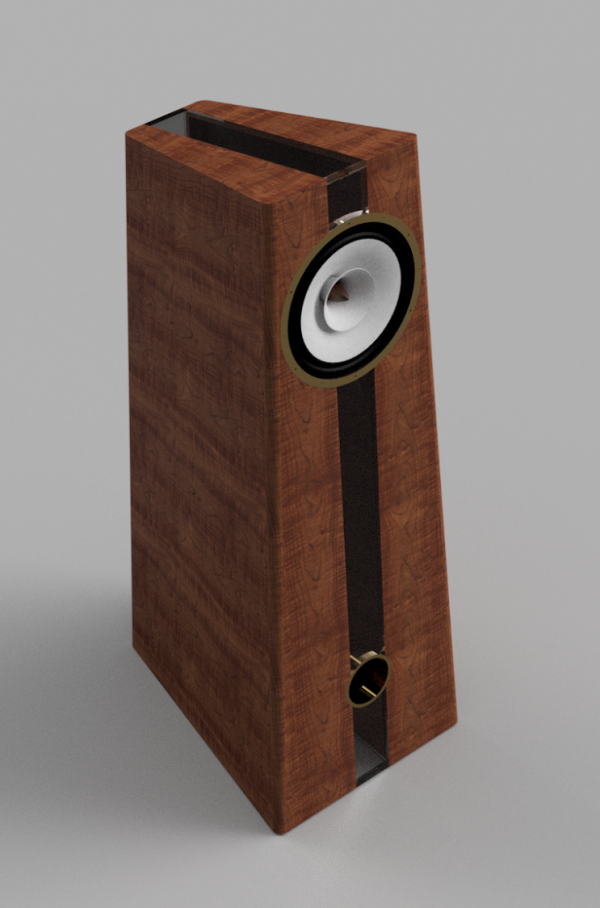

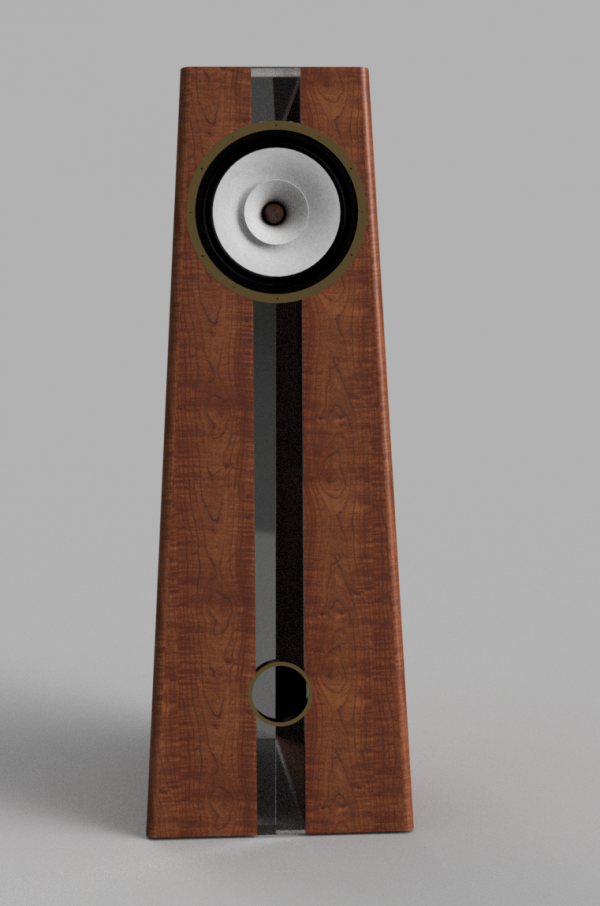

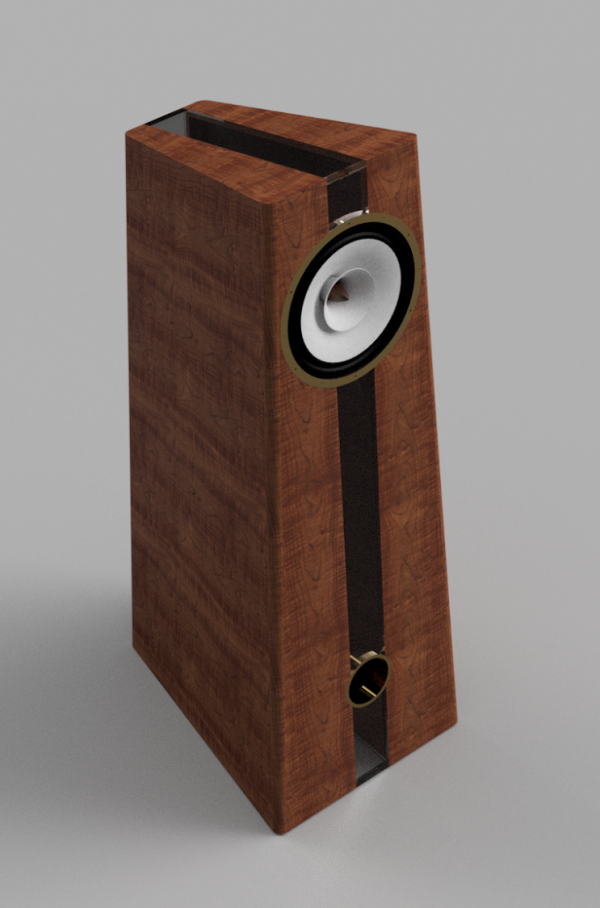

I wanted to showcase the beauty of the field coil, even if it was confined to a cabinet. A thick channel of glass down the middle looked striking, to my eye. Minus a planned-for black granite base, here was that design:

I had the glass waterjet-cut by a local shop, but soon after I'd finished the CAD work I shelved this idea. There were so many unknowns around the basic construction and assembly of it. And, it was a clear violation of my guidelines: it was much too expensive and difficult for a first pass. I still have the CAD files, the toolpaths, and the glass for it in my shop, though. Maybe someday.

The next design was meant to correct for the overwhelming complexity and expense of the first design, and went much too far in that regard:

It didn't even look good... but unfortunately, I was fixated with some of it's features. The wires could be easily concealed with channels and conduits. The motor protruding from the back was all at once good for motor cooling, support, and easy driver removal from the front when necessary. The wood was a beautiful, dense Santos Mahogany, and the sheet glass was much more affordable than the bespoke shapes of the previous design. Drunk on the driver's success, I pushed ahead:

As previously mentioned, wood likes to flex and contract with changes in temperature and humidity. When it is bound by the strongest, stiffest glue one can possibly find to a completely inflexible stratum, the outcome is quite enlightening.

The glass cabinets were about a week from completion.

As I wandered around the house with my first cup of coffee one morning, I turned to hear a very strange screeching noise coming from them. Over the course of the past week or so, the relentlessly flexing wood had finally worn its opponent down. And that terrible sound I was hearing? It was the glass, inevitably surrendering. It happened to both cabinets, on all sides more or less at once, and literally all within an hour's time. This was the picture I texted my wife after a minute or two of helplessly watching the spectacle as it began:

Sad though it was at the time, this setback was a necessary turning point.

I had allowed myself to doubt, and in doing so lost sight of my vision; of why I was pursuing any of this at all. The passion and effort I'd invested so far was about trying to do something for a living that I love. It was not about fear of returning to something that I don't. It was about building the greatest possible loudspeaker that I could make. It was not about trying to build one that I thought I could sell, or that I worried may be imperfect in some all but unforeseeable way, down the road.

It also taught me to prototype iteratively in cheap materials, which of course I should have been doing all along. It brought real discipline back to my process. It woke me up to what an abomination the design actually was, and why. For starters it was insanely top-heavy and one day small, curious children would have been crushed under its falling weight. The motor cooling was superfluous, the port didn't have adequate interior room for it to function well, the sound was thin, the cabinet resonated excessively, and reflections bled through the cone. The parallel surfaces were a masterpiece in standing waves. It lacked baffle diffraction compensation, and there was no way to attractively address cabinet resonances, or to increase apparent volume. What's more, stripped of the flashy glass or simply viewed from any angle other than precisely side-on, well... it wasn't at all beautiful to look at.

Chapfallen, I removed the ruined glass, and finished out the cabinets with darkly stained mahogany:

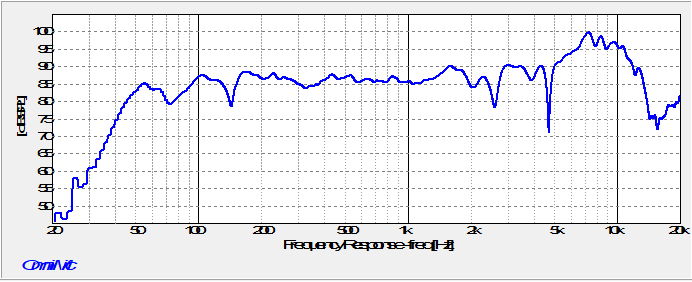

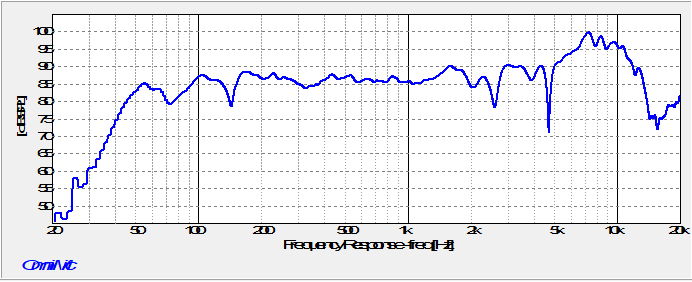

I took steps to raise the total Q at the expense of a little sensitivity, and the "giant iPhones" as they later came to be known measured in OmniMic software thusly:

Very little record of these speakers remains, which leads me to the pro tip for this chapter: exhaustively measure each of your failures, no matter how bad they are. The successes feel wonderful, but it's the failures that are priceless. I have learned more than I can reasonably document here from the analysis of my worst efforts, and next to nothing from my best.

The colossal iPhones were too clever by half. Nonetheless, I took them along with a carload of mid-fi gear and my best subwoofer to that local event the following month, and delivered a lengthy presentation to a packed house that evening about my work, to applause. After the talk, the crowd migrated to an adjacent room, where the speakers played for several hours.

And, much to my surprise, everyone who listened to them loved the way they sounded.

Everyone, that is, except me.

It'd be nice to say that the next thing that happened in this long chronicle was that I brought the same patience, discipline and confidence that went into the driver into the cabinetry as well, and greatness was the inevitable outcome. But what really happened was quite different.

A few of the design concerns that needed to be addressed in the cabinetry were these:

- Heat could pose a problem if the owner, accidentally or otherwise, left the power supplies running indefinitely

- Each driver weighed 30lbs, and needed to be very securely supported

- In securing the driver, the means could not afford to deform the frame by even fractions of a millimeter, thereby misaligning the voice coil.

- The driver needed to be accessible for iteration in development and in the event that it ever needed service. Knowing that the motor would likely be bolted to an internal support of some kind, it could not be simply taken in and out of a conventional cabinet by way of a handful of screws in the flange.

- The design must not be so difficult, time-consuming, or costly to execute as to be impractical

Whatever you do, I thought, don't look at the whole elephant. Just keep your head down, and continue to eat. One little forkful at a time.

A ported design was to be my first, and any outcome that required a subwoofer would be judged a failure. This was full-range, or bust. Right from the outset however, modeling the cabinet made clear that regardless of architecture, bass performance was going to be a challenge. In a ported enclosure that's of course dependent upon box volume and tuning frequency. However, the Thiele Small parameters of the driver are also critically important. A few key values are Fs (the resonant frequency of the driver in free-air), Qts (derived from the electrical and mechanical quality of the driver), and Vas (the volume of air in a cubic meter with equivalent compliance as the driver suspension).

Unsurprisingly, modeling showed that large volumes tuned properly played deep. However, beyond a certain scale enclosures became edifices, too unappealing and imposing. I decided that 120 liters would be my limit, and anything further would need to be achieved by way of "apparent" internal volume.

Low Qts predicted a smooth roll-off, but well above my target in the mid to low 30's. High Qts played significantly deeper, but left a +3dB boost in output just before roll-off, for which impractically lower tuning seemed the only remedy. The otherwise wonderful ultra-soft driver suspension came with ultra-high Vas, which unfortunately predicted a more pronounced hump, and an earlier, steeper roll-off. Every choice it seemed, was a maddening trade-off. The trick was clearly in performing a balancing act between them all.

I wanted to showcase the beauty of the field coil, even if it was confined to a cabinet. A thick channel of glass down the middle looked striking, to my eye. Minus a planned-for black granite base, here was that design:

I had the glass waterjet-cut by a local shop, but soon after I'd finished the CAD work I shelved this idea. There were so many unknowns around the basic construction and assembly of it. And, it was a clear violation of my guidelines: it was much too expensive and difficult for a first pass. I still have the CAD files, the toolpaths, and the glass for it in my shop, though. Maybe someday.

The next design was meant to correct for the overwhelming complexity and expense of the first design, and went much too far in that regard:

It didn't even look good... but unfortunately, I was fixated with some of it's features. The wires could be easily concealed with channels and conduits. The motor protruding from the back was all at once good for motor cooling, support, and easy driver removal from the front when necessary. The wood was a beautiful, dense Santos Mahogany, and the sheet glass was much more affordable than the bespoke shapes of the previous design. Drunk on the driver's success, I pushed ahead:

As previously mentioned, wood likes to flex and contract with changes in temperature and humidity. When it is bound by the strongest, stiffest glue one can possibly find to a completely inflexible stratum, the outcome is quite enlightening.

The glass cabinets were about a week from completion.

As I wandered around the house with my first cup of coffee one morning, I turned to hear a very strange screeching noise coming from them. Over the course of the past week or so, the relentlessly flexing wood had finally worn its opponent down. And that terrible sound I was hearing? It was the glass, inevitably surrendering. It happened to both cabinets, on all sides more or less at once, and literally all within an hour's time. This was the picture I texted my wife after a minute or two of helplessly watching the spectacle as it began:

Sad though it was at the time, this setback was a necessary turning point.

I had allowed myself to doubt, and in doing so lost sight of my vision; of why I was pursuing any of this at all. The passion and effort I'd invested so far was about trying to do something for a living that I love. It was not about fear of returning to something that I don't. It was about building the greatest possible loudspeaker that I could make. It was not about trying to build one that I thought I could sell, or that I worried may be imperfect in some all but unforeseeable way, down the road.

It also taught me to prototype iteratively in cheap materials, which of course I should have been doing all along. It brought real discipline back to my process. It woke me up to what an abomination the design actually was, and why. For starters it was insanely top-heavy and one day small, curious children would have been crushed under its falling weight. The motor cooling was superfluous, the port didn't have adequate interior room for it to function well, the sound was thin, the cabinet resonated excessively, and reflections bled through the cone. The parallel surfaces were a masterpiece in standing waves. It lacked baffle diffraction compensation, and there was no way to attractively address cabinet resonances, or to increase apparent volume. What's more, stripped of the flashy glass or simply viewed from any angle other than precisely side-on, well... it wasn't at all beautiful to look at.

Chapfallen, I removed the ruined glass, and finished out the cabinets with darkly stained mahogany:

I took steps to raise the total Q at the expense of a little sensitivity, and the "giant iPhones" as they later came to be known measured in OmniMic software thusly:

Very little record of these speakers remains, which leads me to the pro tip for this chapter: exhaustively measure each of your failures, no matter how bad they are. The successes feel wonderful, but it's the failures that are priceless. I have learned more than I can reasonably document here from the analysis of my worst efforts, and next to nothing from my best.

The colossal iPhones were too clever by half. Nonetheless, I took them along with a carload of mid-fi gear and my best subwoofer to that local event the following month, and delivered a lengthy presentation to a packed house that evening about my work, to applause. After the talk, the crowd migrated to an adjacent room, where the speakers played for several hours.

And, much to my surprise, everyone who listened to them loved the way they sounded.

Everyone, that is, except me.

Last edited by a moderator: