Subjective disappointments aside, it felt good that next morning having managed a public speaking engagement, and successful listening event. Some said that they'd never heard anything better. Others were impressed with the craftsmanship. More than a few had asked the price.

Them: "These speakers are amazing! What's the price?"

Me: "Thanks! I'm trying my best to keep them under twenty thousand."

Them: <long pause> "Dollars..?"

Watches were checked, polite excuses made... that was the end of our conversation.

My wife was the first between us to discover the audio shows. There was so much we didn't know, and it was clear that to get an education, we'd need to attend a few of them. She booked the travel arrangements, and suddenly we were off to the 2018 Capital Audiofest.

CAF was the perfect first show for us to attend. It had an easy, family-friendly vibe, in contrast to the hyper-corporate confection we'd expected. Sure, there were polished marketing machines, but there were plenty of small producers offering hand-crafted work too, often at price points north of anything I had yet considered.

The people were warm and friendly, of which there are too many to mention here. The first exhibitor I ever spoke with at a show was Brian of Charney Audio. He suggested that they design and build cabinets for us, an almost irresistible offer at the time. I met Ze'ev Schlick of Pure Audio Project, who I continued to correspond with about my work long after the show. John Wolff of Classic Audio Loudspeakers played Billie Jean on reel-to-reel for me, so loudly that the opening snare strike made me physically jump out of my chair as his collection of RCA dogs looked on, questioningly.

Months later, we went to the Rocky Mountain Audiofest. There I met Chris Brunhaver of PS Audio, who has answered every email I've ever sent him since, no matter how silly, connecting me to the right resources and giving his thoughtful advice. Steven Norber of Prana Fidelity and his wife showed a speaker he'd thrown together over the prior weekend, and that remains among the best I've ever heard at the shows these past years. Shortly after RMAF, I met David Angress at a small audio event in Portland, Chairman of ADAM Audio in Germany at the time. It was David who urged me to submit a patent on the spider.

Lastly, at those first shows and events, I heard full-range and field coil drivers considered to be among the very best examples in the world. And that, just like the amazing people I'd met, inspired me to push on.

With that in mind, it was time to return to the drawing board. Before Songer Audio was even a twinkle in my eye, I'd made these:

They were one of several designs I'd made around the Tang Band W8-1772 driver. It was elegant in its own way, and it solved the problems that had surfaced in my bold but flawed first try. The CAD work went quickly; an internal shelf was added to support the weight of the driver, and a simple access panel in the back for easy swapping and service. A crude prototype in birch ply initially vetted the design - there was to be no guessing or self-delusion, this time around. I learned all that I could from it, and then moved on to a first production prototype, in cherry.

They were finished out with polished brass hardware, and a nice lacquer finish over a cherry stain.

I hoped that the tonal character of the cherry wood may be pleasing, and only lined about 60% of the interior. There were no other treatments inside the cabinet, and 4dB of baffle step compensation at 1.2kHz. A new version of the driver was developed with higher efficiency, clocking in at about 99dB 1W/1m:

The Qts was still too low, and the inductance too high. To address the former, I'd learned that Qts can be variably increased with the addition of a series resistor on the positive lead of the driver. I'd give up some efficiency in doing so, but in theory push the Qts high enough for acceptable bass performance.

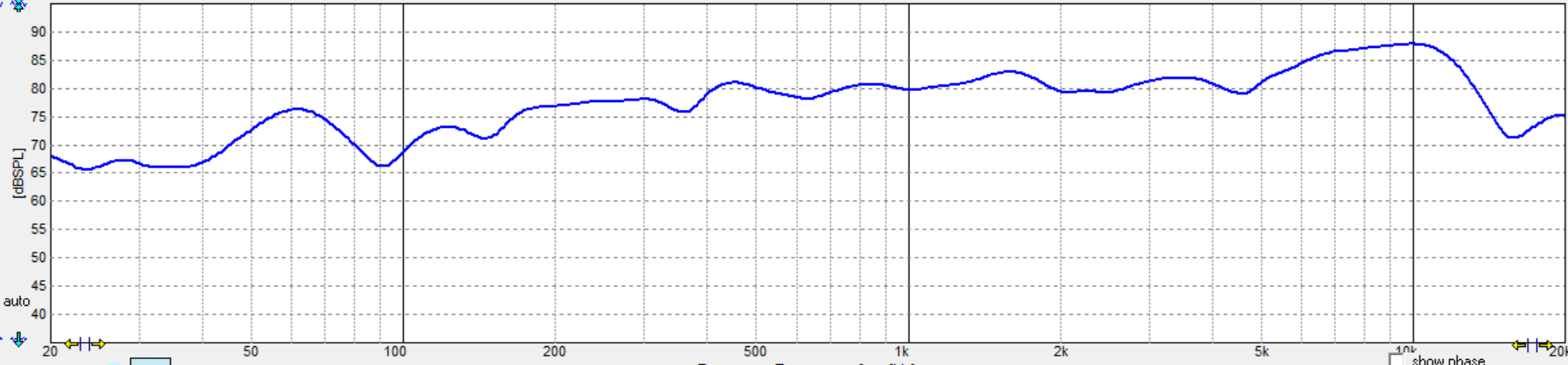

And it worked. Here's a smoothed response with 15 Ohms of series resistance, a single speaker at a meter, driver height, on axis:

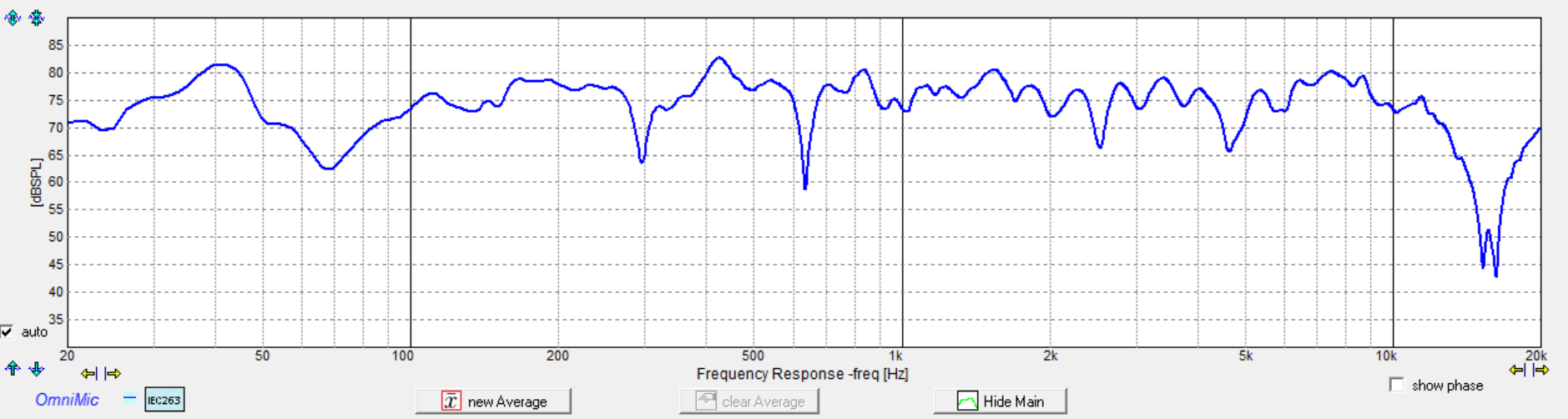

This is both speakers, 1/96 octave at 7 feet, toed out about 15 degrees off-axis from the listening position:

It wasn't perfect, certainly. I mean, feast your eyes on that strange suckout drifting between 90 - 70Hz. If you were hoping for any treble past 12kHz, you're in for a disappointment. But that said... this result was a giant stride forward. A subwoofer was now unnecessary for satisfying levels of bass performance. While some claim to perceive treble beyond the limits of age-related loss, by way of the eyes or skin, I've never discovered any such gifts in myself. When I check my hearing with a tone generator, I'm deaf as a post at 10kHz and beyond. The last octave is well worth striving for nonetheless, and I was never going to reach it unless I found a way to significantly reduce driver inductance.

At about this time, the makerspace I'd been using as my shop fell on hard times, and shuttered. I suddenly lost access to my studio, fully-outfitted professional wood and metal shops, and a thriving community of similarly afflicted creative individuals, like myself. That might have spelled an end to the dream as well, had it not been for my best friend, Andrew. Even though he had nothing more to offer than his circa-1940's single-car garage, he not only gave me the key and unfettered 24/7 access to it, he bought a basic CNC router for me to use, as well. I am still amazed and humbled by it, to this day.

In the following months, it was in the seasonal freezing cold and boiling heat of that tiny garage, a riot of OSHA violations likely unparalleled anywhere on earth, that the first true S1 was born.

Them: "These speakers are amazing! What's the price?"

Me: "Thanks! I'm trying my best to keep them under twenty thousand."

Them: <long pause> "Dollars..?"

Watches were checked, polite excuses made... that was the end of our conversation.

My wife was the first between us to discover the audio shows. There was so much we didn't know, and it was clear that to get an education, we'd need to attend a few of them. She booked the travel arrangements, and suddenly we were off to the 2018 Capital Audiofest.

CAF was the perfect first show for us to attend. It had an easy, family-friendly vibe, in contrast to the hyper-corporate confection we'd expected. Sure, there were polished marketing machines, but there were plenty of small producers offering hand-crafted work too, often at price points north of anything I had yet considered.

The people were warm and friendly, of which there are too many to mention here. The first exhibitor I ever spoke with at a show was Brian of Charney Audio. He suggested that they design and build cabinets for us, an almost irresistible offer at the time. I met Ze'ev Schlick of Pure Audio Project, who I continued to correspond with about my work long after the show. John Wolff of Classic Audio Loudspeakers played Billie Jean on reel-to-reel for me, so loudly that the opening snare strike made me physically jump out of my chair as his collection of RCA dogs looked on, questioningly.

Months later, we went to the Rocky Mountain Audiofest. There I met Chris Brunhaver of PS Audio, who has answered every email I've ever sent him since, no matter how silly, connecting me to the right resources and giving his thoughtful advice. Steven Norber of Prana Fidelity and his wife showed a speaker he'd thrown together over the prior weekend, and that remains among the best I've ever heard at the shows these past years. Shortly after RMAF, I met David Angress at a small audio event in Portland, Chairman of ADAM Audio in Germany at the time. It was David who urged me to submit a patent on the spider.

Lastly, at those first shows and events, I heard full-range and field coil drivers considered to be among the very best examples in the world. And that, just like the amazing people I'd met, inspired me to push on.

With that in mind, it was time to return to the drawing board. Before Songer Audio was even a twinkle in my eye, I'd made these:

They were one of several designs I'd made around the Tang Band W8-1772 driver. It was elegant in its own way, and it solved the problems that had surfaced in my bold but flawed first try. The CAD work went quickly; an internal shelf was added to support the weight of the driver, and a simple access panel in the back for easy swapping and service. A crude prototype in birch ply initially vetted the design - there was to be no guessing or self-delusion, this time around. I learned all that I could from it, and then moved on to a first production prototype, in cherry.

They were finished out with polished brass hardware, and a nice lacquer finish over a cherry stain.

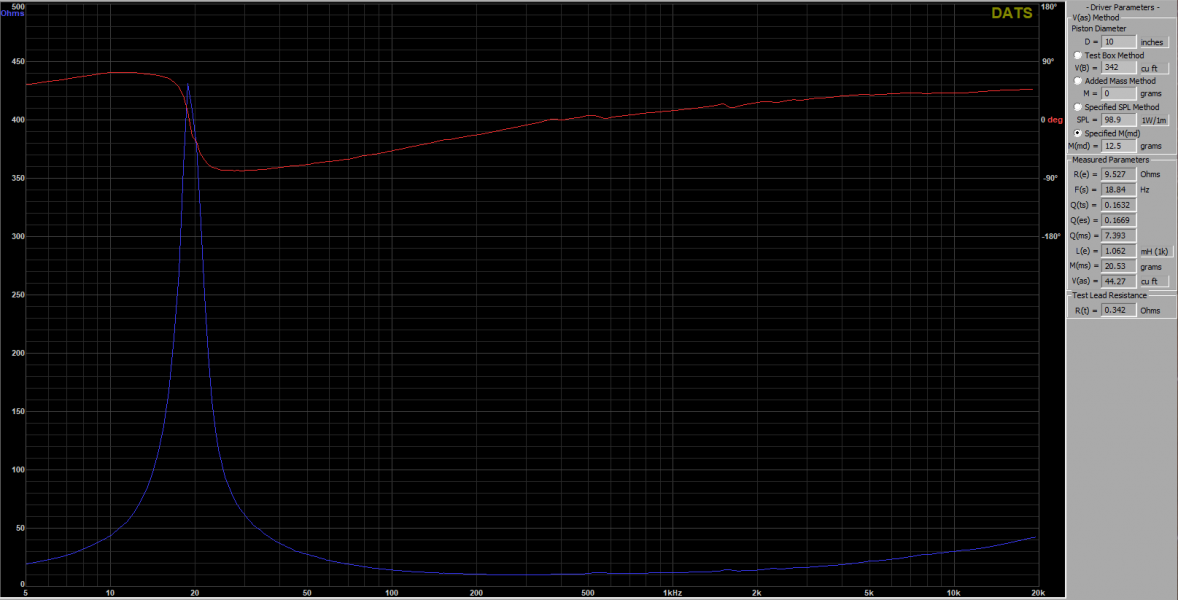

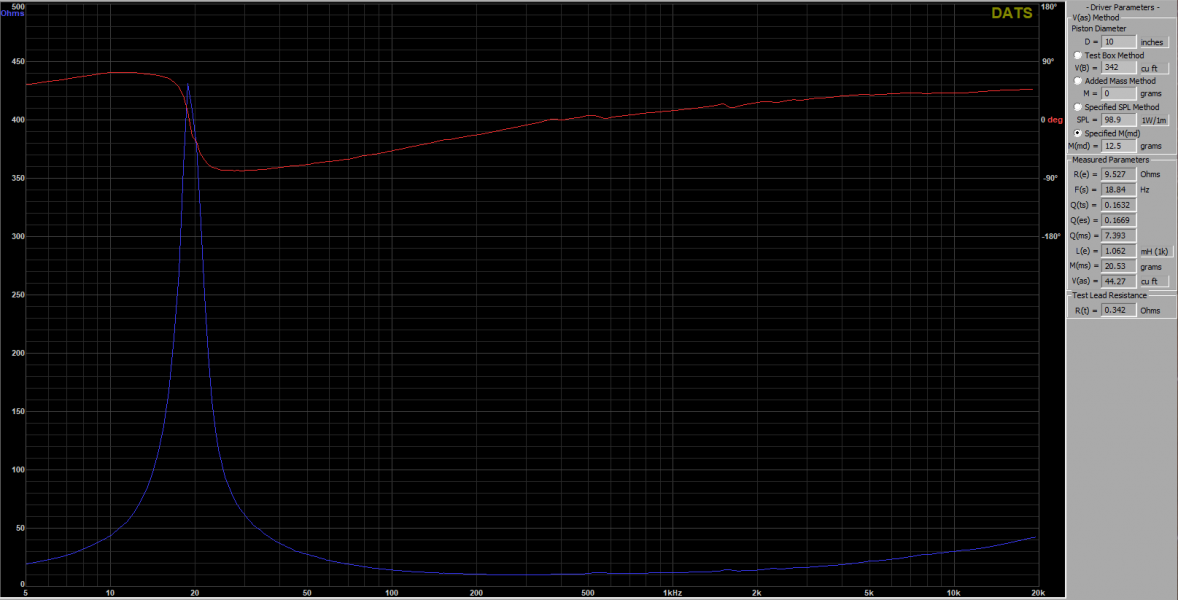

I hoped that the tonal character of the cherry wood may be pleasing, and only lined about 60% of the interior. There were no other treatments inside the cabinet, and 4dB of baffle step compensation at 1.2kHz. A new version of the driver was developed with higher efficiency, clocking in at about 99dB 1W/1m:

The Qts was still too low, and the inductance too high. To address the former, I'd learned that Qts can be variably increased with the addition of a series resistor on the positive lead of the driver. I'd give up some efficiency in doing so, but in theory push the Qts high enough for acceptable bass performance.

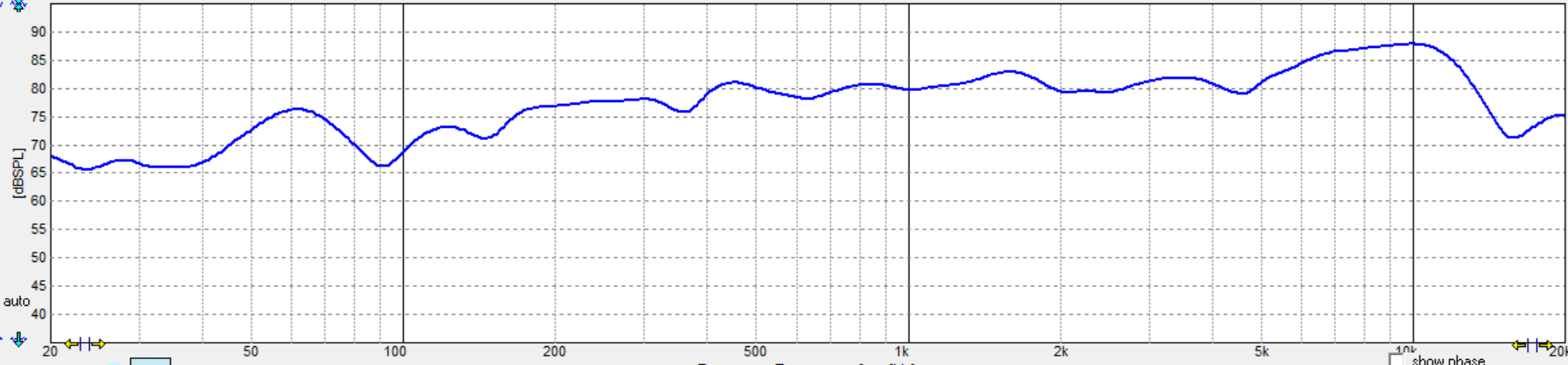

And it worked. Here's a smoothed response with 15 Ohms of series resistance, a single speaker at a meter, driver height, on axis:

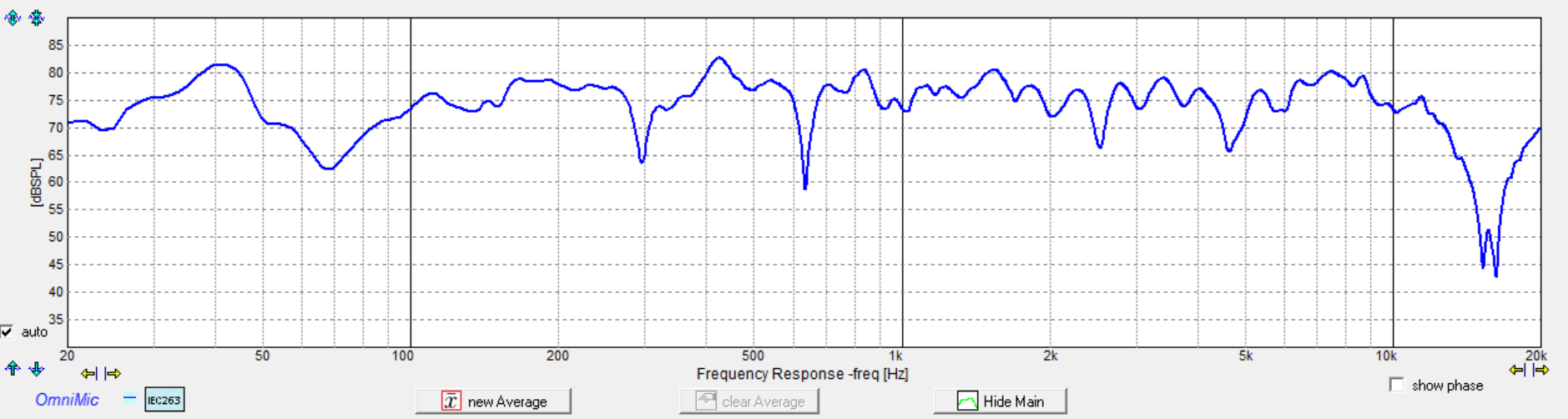

This is both speakers, 1/96 octave at 7 feet, toed out about 15 degrees off-axis from the listening position:

It wasn't perfect, certainly. I mean, feast your eyes on that strange suckout drifting between 90 - 70Hz. If you were hoping for any treble past 12kHz, you're in for a disappointment. But that said... this result was a giant stride forward. A subwoofer was now unnecessary for satisfying levels of bass performance. While some claim to perceive treble beyond the limits of age-related loss, by way of the eyes or skin, I've never discovered any such gifts in myself. When I check my hearing with a tone generator, I'm deaf as a post at 10kHz and beyond. The last octave is well worth striving for nonetheless, and I was never going to reach it unless I found a way to significantly reduce driver inductance.

At about this time, the makerspace I'd been using as my shop fell on hard times, and shuttered. I suddenly lost access to my studio, fully-outfitted professional wood and metal shops, and a thriving community of similarly afflicted creative individuals, like myself. That might have spelled an end to the dream as well, had it not been for my best friend, Andrew. Even though he had nothing more to offer than his circa-1940's single-car garage, he not only gave me the key and unfettered 24/7 access to it, he bought a basic CNC router for me to use, as well. I am still amazed and humbled by it, to this day.

In the following months, it was in the seasonal freezing cold and boiling heat of that tiny garage, a riot of OSHA violations likely unparalleled anywhere on earth, that the first true S1 was born.

Last edited: