Stimmt Pauls Geschichtsstunde, dass Hornlautsprecher als Lösung für das Problem entwickelt wurden, dass frühe Verstärker nur wenige Watt erzeugen konnten?

Hello Ron, even if the answer comes a little late.

In a period during the infancy of the gramophone, when it was universally employed, the horn loudspeaker gained increasing prominence, and its development advanced steadily. From 1887, when Emil Berliner invented the gramophone, to the golden era of the late 1920s, when Western Electric in the USA and Klangfilm in Europe began designing some of the most iconic horn loudspeakers in history, the pursuit of perfect sound was relentless.

However, after the heyday of cinema, the popularity of horn loudspeakers declined—likely due to their large size, the complexity of their manufacture, and consequently their high cost. The trend toward smaller living spaces certainly played a role as well. Today, while full-range horn systems are embraced only by a small circle of enthusiasts, most experts unanimously recognize their unparalleled virtues as loudspeaker enclosures, especially their exceptional realism and “presence.”

But let us take a look back at their origins.

The 1920s marked a period of unprecedented prosperity in the United States and Europe. Enormous resources were devoted to advancing sound reproduction technology across various domains: telephones, microphones, record-making processes, radio, and, most notably, talking motion pictures. Films were as central to daily life then as television and the internet are today. In major cities, newsreel theaters operated around the clock, much like 24/7 television channels. The invention of “talkies,” or movies with synchronized sound, was a groundbreaking event that permanently transformed film and media.

Two colossal corporations, RCA and Western Electric, dominated American and global communication technology for much of the 20th century. They were responsible for numerous innovations that underpin modern life, from the telephone system to record technology (pioneered by RCA under its Victrola brand), television, and even the VCR. Both companies played crucial roles in the foundational development of sound for motion pictures.

Theaters of that era were nothing like the multiplexes of today. They were grand, cavernous spaces, often seating thousands of patrons. With upholstered seats, heavy drapery, and audiences that absorbed significant sound, achieving effective sound reproduction posed a formidable challenge. The demand for loudness was immense, but the amplifiers of the time, relying on simple vacuum tube triodes, produced very limited power—typically no more than 10 watts per amplifier. Even with multiple amplifiers (which were large and expensive), the total power available to deliver credible sound in a vast theater was minuscule compared to even the most basic modern amplifiers. So how did they transform such modest power into impressive sound?

The answer was horns.

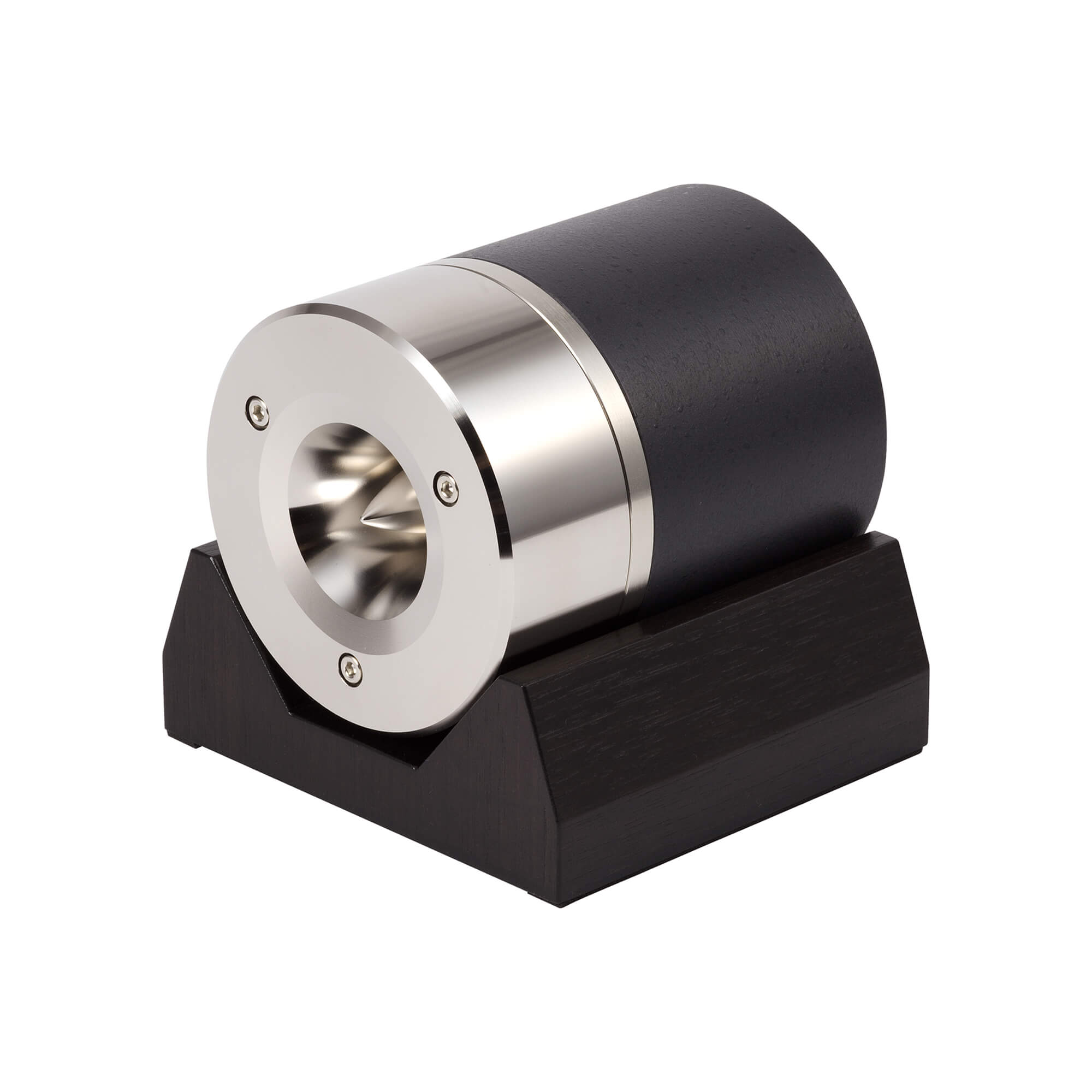

Horns themselves were not a new invention, but engineers at Bell Labs, Western Electric (notably Wente, Thuras, and Fletcher), and RCA (Volkman, Masa, and Olson) elevated horn technology to extraordinary heights. Their designs—such as

Western Electric 15A or the 13A, and later the 22A—were monumental structures, typically positioned behind theater screens. These horn-loaded loudspeakers were so efficient that they could convert the limited power of triode amplifiers into plausible, realistic sound levels, even in the largest theaters.

In Europe, a few years later, Klangfilm achieved similar feats with systems like the Bionor and Eurodyn. Without the aid of computers, these engineers solved complex acoustical and psycho-acoustical challenges that remain difficult even with today’s advanced technology. Their achievements were nothing short of miraculous.

With the onset of the Great Depression and advances in amplifier technology, the necessity and popularity of large horn loudspeakers gradually diminished. By the mid-20th century, horns were nearly extinct, with few exceptions such as Klipsch. The development of the transistor by Bell Labs under Shockley, Bardeen, and Brattain in 1948 introduced new possibilities, though the sound quality of early transistor amplifiers was far from ideal. Even Klipsch eventually succumbed to market pressures, producing smaller, more economically viable designs. The once-proud kings of cinema were folded, both literally and figuratively, into compact horn systems suitable for living rooms.

However, these folded designs introduced unavoidable compromises, particularly above frequencies of 200 Hz. The misconception that greater excursion (x-max) and power can compensate for reduced cabinet volume remains one of the biggest obstacles to achieving perfect sound. Yet, shouldn’t perfect sound—the “holy grail” of audio—be our ultimate goal?