Agree on the experience I have had with DorianDorian Records is sadly no more, but they produced some of the most beautiful recordings I’ve heard. This lovely choral album is no exception. The voices sound incredibly natural on the big SL’s with the organ gently filling in the deep bass in the background. A masterclass in how to record a choral performance.

Hymns of Heaven & Earth - Saint Clement's Choi... | AllMusic

Hymns of Heaven & Earth by Saint Clement's Choir, Peter Richard Conte released in 1998. Find album reviews, track lists, credits, awards and more a...www.allmusic.com

Soundlab Audiophile G9-7c: a 30-year odyssey fulfilled

- Thread starter godofwealth

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Thanks! Just bought the complete BIS set of symphonies and string works after your comments and speed reading about 10 reviews…was just listening to Mendelssohn (CPO label) annd also have read a little of his impressive background as a child prodigy. Was also recently invited to hear his Elijah by the LSO conducted by Sir Anthony Pappano.Mendelssohn was a child prodigy who wrote astonishingly good music at a very early age. His string symphonies are a great example of his precocity. This superlative recording from BIS sounds gorgeous on the big SL’s. I had earlier thought incorrectly that this recording was a bit brightly lit while listening to it on my Quads. I was wrong. On the SL G9-7c, the strings are rich, and gorgeous sounding. It bears repeating. The speakers ultimately are the medium through which you hear everything. Get that right, and a lot of other issues go away.

View attachment 139626

Last edited:

Johann Sebastian Bach had many sons, some of whom turned out to be illustrious composers in their right. J.C. Bach was one of those whose delightful chamber music forms the basis for this beautifully recorded album from DG Archiv. I have played the original CD so many times that I probably burned holes in the CD pits from the laser beam.

The opening quintet features a flute, violin, cello, oboe and harpsichord. The textures are lovely on the big SL’s, sounding considerably more refined than the somewhat cruder and brighter presentation on my Quads 2905’s. There’s an element of elegance in how each instrument is presented without harshness, even though this is an original instruments recording. The flute soars on the extreme left, the harpsichord in the middle appropriately recessed and the violin between the two on the left. The cello on the right is recorded without inflating its sound. In the second movement, the cello plays an almost Schubertian elegiac melody.

In listening to this album, we clearly hear where Mozart derived his inspiration from as this could have indeed been written by that Salzburg genius. We are beyond Johann’s own world and bridging to a new world of music here. Highly recommended. A desert island disc.

The opening quintet features a flute, violin, cello, oboe and harpsichord. The textures are lovely on the big SL’s, sounding considerably more refined than the somewhat cruder and brighter presentation on my Quads 2905’s. There’s an element of elegance in how each instrument is presented without harshness, even though this is an original instruments recording. The flute soars on the extreme left, the harpsichord in the middle appropriately recessed and the violin between the two on the left. The cello on the right is recorded without inflating its sound. In the second movement, the cello plays an almost Schubertian elegiac melody.

In listening to this album, we clearly hear where Mozart derived his inspiration from as this could have indeed been written by that Salzburg genius. We are beyond Johann’s own world and bridging to a new world of music here. Highly recommended. A desert island disc.

One fascinating aspect of the large panels in my G9-7c Soundlab’s is how they dissect each recording to its bones, but in a nice way that reveals potential issues with how microphones were placed, but not distract from the enjoyment of the music. The above DG Archiv recording is closely miked. The instruments sound a bit larger than life. But that’s appropriate here for a chamber music piece. It sounds like the musicians are playing in my listening room. In J.C. Bach’s time, that’s very likely how most of the connoisseurs of music would have heard the piece. Often stereo reproduction involves a semicircular stage where instruments in the middle get recessed and those on the extreme left or right get pushed out in front. Jonathan Valinsky in a review in TAS spoke eloquently about how ARC preamplifiers and amplifiers tended to accentuate this presentation by adding some tube bloom to the sound. Here the large panels sound like they’re doing something similar, adding a blossoming of the sound, even though I’m playing this recording on my Mola Mola solid state electronics.

One often neglected part of high end audio is ways to enhance the direct sound one hears from the speakers alone and minimize what one hears from the colorations added by the room. I’ve seen countless pictures of listening rooms that are long and narrow, with large multidriver moving coil dynamic box speakers placed along the short wall on one end with the listening chair at the other end of the room. Certain well-known reviewers from Stereophile and TAS have exactly such a setup. In such cases it’s almost guaranteed that the room is adding a huge amount of coloration to the sound. Recipe for disaster! Avoid.

In my case I minimize this room induced coloration in several ways. First electrostatics like my large SL’s tend to greatly reduce lateral sidewall reflections and floor and ceiling artifacts from clouding the sound. Second, my speakers are placed widely apart along the long wall and far away from it (to accommodate the huge panels, my room is large). Finally, I sit up fairly close given the size of the speakers. This guarantees that most of what I’m hearing is the direct sound from the speakers, not the delayed room reflections. Of course, sound travels in all directions and room reflections can never be eliminated unless you listen in an anechoic chamber. But the human ear is a marvelous instrument that over millions of years of evolution has adapted to sort out the zillions of sounds and localize the initial arrival. Failure to do so in the jungle would mean instant death from an approaching predator. A twig snaps. You’re a tiny rabbit and you have a few seconds or less to figure out where it came from.

So, if you configure your room right, you can greatly improve the sound you hear on recordings to favor the venue recorded on the album, not your room. Sit as close as possible, use speakers that reduce sidewall reflections and of course use plenty of room dampening material. I have lots of overstuffed sofas, large cushions and carpet to reduce and absorb the sound. Wooden floors are nice to look at in realtor brochures but the kiss of death in high end audio.

In my case I minimize this room induced coloration in several ways. First electrostatics like my large SL’s tend to greatly reduce lateral sidewall reflections and floor and ceiling artifacts from clouding the sound. Second, my speakers are placed widely apart along the long wall and far away from it (to accommodate the huge panels, my room is large). Finally, I sit up fairly close given the size of the speakers. This guarantees that most of what I’m hearing is the direct sound from the speakers, not the delayed room reflections. Of course, sound travels in all directions and room reflections can never be eliminated unless you listen in an anechoic chamber. But the human ear is a marvelous instrument that over millions of years of evolution has adapted to sort out the zillions of sounds and localize the initial arrival. Failure to do so in the jungle would mean instant death from an approaching predator. A twig snaps. You’re a tiny rabbit and you have a few seconds or less to figure out where it came from.

So, if you configure your room right, you can greatly improve the sound you hear on recordings to favor the venue recorded on the album, not your room. Sit as close as possible, use speakers that reduce sidewall reflections and of course use plenty of room dampening material. I have lots of overstuffed sofas, large cushions and carpet to reduce and absorb the sound. Wooden floors are nice to look at in realtor brochures but the kiss of death in high end audio.

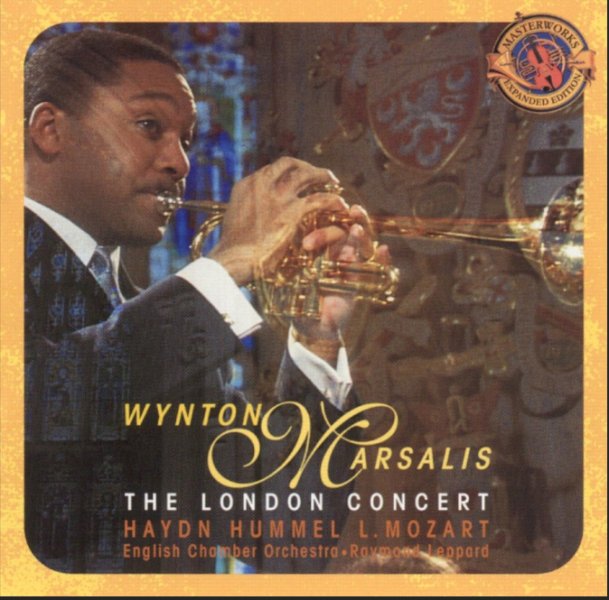

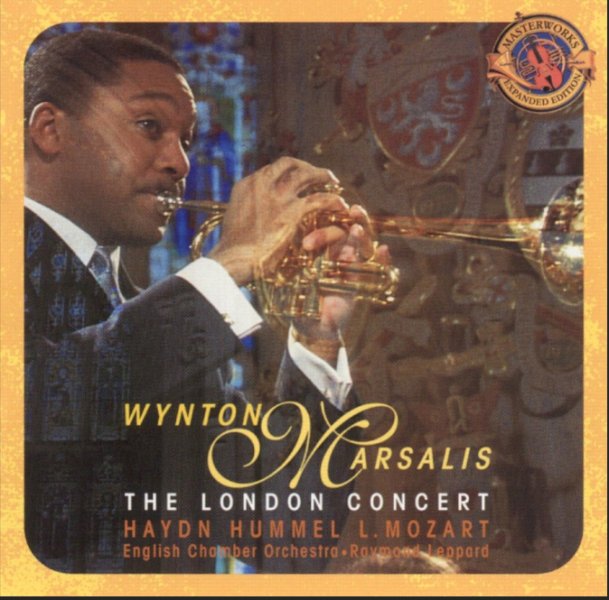

Wynton Marsalis is a rara avis (rare bird in Latin), one equally at home playing classical or jazz. Here we hear him in a Sony DSD recording made 30 years ago in 1993 of trumpet concertos by famous composers like Joseph Haydn. The recording sounds inappropriately sumptuous if you’re a diehard original instruments devotee. But I’m not. Marsalis’ tone is luxuriant and rich. He’s brilliant in tone when he needs to be. And thank heavens, the trumpet is appropriately miked in an ambient concert hall space, not spotlit in a studio. The luxuriant strings of the English Chamber Orchestra might displease Sir Roger Norrington and like-minded period instrument conductors. But I’m broad minded to enjoy music that’s tailored to modern instruments. I’d rather hear Beethoven on a concert grand rather than a fortepiano. However, I do admit Bach sound better sometimes on a harpsichord than a modern piano.

What an absolutely lovely trumpet concerto Haydn wrote. The slow movement has this beguiling melody that will make your heart swoon. Mozart undoubtedly got much of his melody from Haydn. And so did Beethoven. The wise Haydn, always agreeable to the wishes of his employer, the Archduke, never displeased him. He wrote music on command. His royal benefactor played the baryton, an old type of cello. So, Haydn diligently wrote scores of baryton trios to please his employer. He consequently never wanted for money. And unlike the firebrand Beethoven or haughty Mozart who thought himself superior to every musician in Vienna (see the movie Amadeus), Haydn found the time to write great music as well as please his employer. Good lesson to learn even today. This concerto written in 1796 must have thrilled Beethoven when he heard it, although the latter never wrote one. On the big SL, the trumpet sounds divine. Bright when it needs to be, but not melt-your-ears-metallic-tweeter bright.

What an absolutely lovely trumpet concerto Haydn wrote. The slow movement has this beguiling melody that will make your heart swoon. Mozart undoubtedly got much of his melody from Haydn. And so did Beethoven. The wise Haydn, always agreeable to the wishes of his employer, the Archduke, never displeased him. He wrote music on command. His royal benefactor played the baryton, an old type of cello. So, Haydn diligently wrote scores of baryton trios to please his employer. He consequently never wanted for money. And unlike the firebrand Beethoven or haughty Mozart who thought himself superior to every musician in Vienna (see the movie Amadeus), Haydn found the time to write great music as well as please his employer. Good lesson to learn even today. This concerto written in 1796 must have thrilled Beethoven when he heard it, although the latter never wrote one. On the big SL, the trumpet sounds divine. Bright when it needs to be, but not melt-your-ears-metallic-tweeter bright.

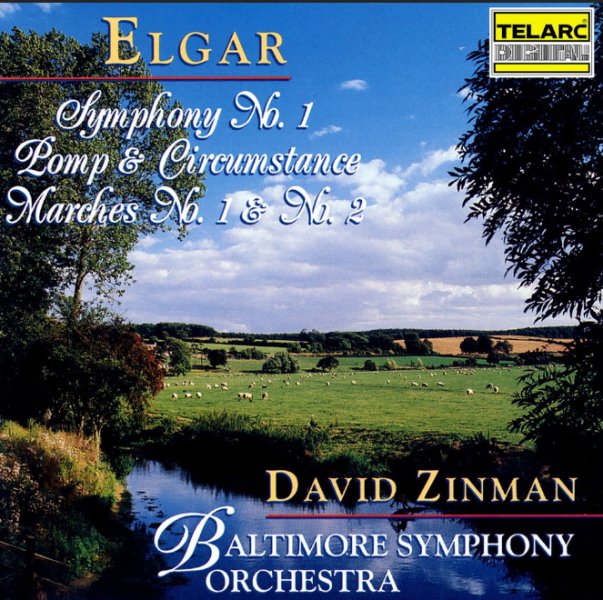

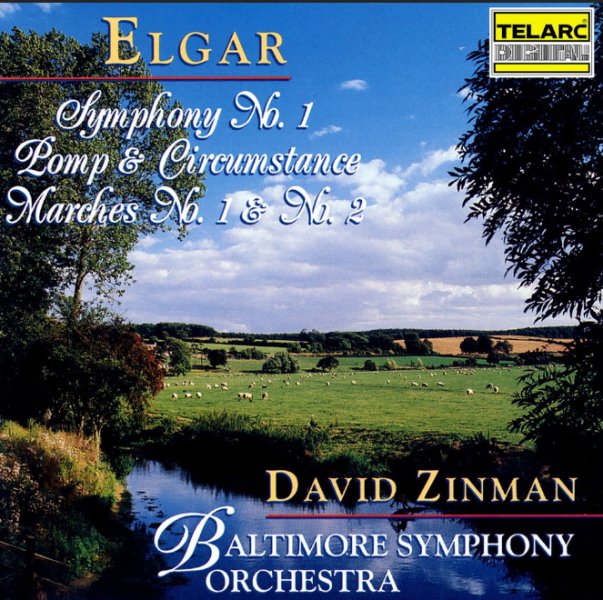

The Brits were a cocky bunch at the end of the 19th century. They ruled over an empire where the sun never set. They were the master of the high seas with an unmatched naval force. Their scientists from Isaac Newton to Charles Darwin to Maxwell dominated science. Their steam engines and railroads were the envy of all. Michael Faraday invented electricity. What’s not to like?

For all their prowess, they had one glaring concern. They longed for a composer who could command adulation like Beethoven. All hope seemed lost till salvation arrived in the form of Elgar. His Enigma Variations set the English musical world ablaze. But where was his symphony? They waited and waited. And waited. Finally Elgar delivered his Symphony No 1. And it was a whopper. Finally a symphony made in Britian that could compare with Beethoven and Brahms.

This magisterial recording from Telarc in its golden years under Jack Renner’s recording brilliance shows what a great symphony it was. Elgar hit a home run when he needed to. A nation yearning for musical salvation found its prayers answered. His Pomp and Circumstance march further sealed his reputation as England’s finest composer. When the Pomp and Circumstance march was first performed live, the audience was so enraptured they demanded an encore. The orchestra complied to only be forced to do yet another one. The conductor remarked that it became a complete nuisance as the concert could not continue with other pieces. And so it has become the mainstay of the legendary BBC Proms each year at Covent Garden, which would be unthinkable without a roaring performance of the Pomp and Circumstance March at the end of each season complete with the standing audience adding their dance movements.

This glorious recording shows that even humble 16-bit audio is more than sufficient to reproduce the dynamics of an orchestra with stunning bass drum impact and the golden sound of brass. Telarc never matched the heights they reached in their early years under Jack Renner and his simple three point microphones as they sadly succumbed to the temptations of massive multimiking in later years.

On the big SL’s, the orchestra sounds majestic and commanding. The bass drum is powerful but not subwoofer bloated. It’s fast and the transient hits you and it’s gone within a few hundred milliseconds. Like in a concert hall, you are not left with that slow dynamic loudspeaker box bass response which lingers on like a bad hangover.

Great way to listen to why Elgar was so revered in Britain at the beginning of the 20th century.

For all their prowess, they had one glaring concern. They longed for a composer who could command adulation like Beethoven. All hope seemed lost till salvation arrived in the form of Elgar. His Enigma Variations set the English musical world ablaze. But where was his symphony? They waited and waited. And waited. Finally Elgar delivered his Symphony No 1. And it was a whopper. Finally a symphony made in Britian that could compare with Beethoven and Brahms.

This magisterial recording from Telarc in its golden years under Jack Renner’s recording brilliance shows what a great symphony it was. Elgar hit a home run when he needed to. A nation yearning for musical salvation found its prayers answered. His Pomp and Circumstance march further sealed his reputation as England’s finest composer. When the Pomp and Circumstance march was first performed live, the audience was so enraptured they demanded an encore. The orchestra complied to only be forced to do yet another one. The conductor remarked that it became a complete nuisance as the concert could not continue with other pieces. And so it has become the mainstay of the legendary BBC Proms each year at Covent Garden, which would be unthinkable without a roaring performance of the Pomp and Circumstance March at the end of each season complete with the standing audience adding their dance movements.

This glorious recording shows that even humble 16-bit audio is more than sufficient to reproduce the dynamics of an orchestra with stunning bass drum impact and the golden sound of brass. Telarc never matched the heights they reached in their early years under Jack Renner and his simple three point microphones as they sadly succumbed to the temptations of massive multimiking in later years.

On the big SL’s, the orchestra sounds majestic and commanding. The bass drum is powerful but not subwoofer bloated. It’s fast and the transient hits you and it’s gone within a few hundred milliseconds. Like in a concert hall, you are not left with that slow dynamic loudspeaker box bass response which lingers on like a bad hangover.

Great way to listen to why Elgar was so revered in Britain at the beginning of the 20th century.

Wow great post! Thank you.The Brits were a cocky bunch at the end of the 19th century. They ruled over an empire where the sun never set. They were the master of the high seas with an unmatched naval force. Their scientists from Isaac Newton to Charles Darwin to Maxwell dominated science. Their steam engines and railroads were the envy of all. Michael Faraday invented electricity. What’s not to like?

For all their prowess, they had one glaring concern. They longed for a composer who could command adulation like Beethoven. All hope seemed lost till salvation arrived in the form of Elgar. His Enigma Variations set the English musical world ablaze. But where was his symphony? They waited and waited. And waited. Finally Elgar delivered his Symphony No 1. And it was a whopper. Finally a symphony made in Britian that could compare with Beethoven and Brahms.

This magisterial recording from Telarc in its golden years under Jack Renner’s recording brilliance shows what a great symphony it was. Elgar hit a home run when he needed to. A nation yearning for musical salvation found its prayers answered. His Pomp and Circumstance march further sealed his reputation as England’s finest composer. When the Pomp and Circumstance march was first performed live, the audience was so enraptured they demanded an encore. The orchestra complied to only be forced to do yet another one. The conductor remarked that it became a complete nuisance as the concert could not continue with other pieces. And so it has become the mainstay of the legendary BBC Proms each year at Covent Garden, which would be unthinkable without a roaring performance of the Pomp and Circumstance March at the end of each season complete with the standing audience adding their dance movements.

This glorious recording shows that even humble 16-bit audio is more than sufficient to reproduce the dynamics of an orchestra with stunning bass drum impact and the golden sound of brass. Telarc never matched the heights they reached in their early years under Jack Renner and his simple three point microphones as they sadly succumbed to the temptations of massive multimiking in later years.

On the big SL’s, the orchestra sounds majestic and commanding. The bass drum is powerful but not subwoofer bloated. It’s fast and the transient hits you and it’s gone within a few hundred milliseconds. Like in a concert hall, you are not left with that slow dynamic loudspeaker box bass response which lingers on like a bad hangover.

Great way to listen to why Elgar was so revered in Britain at the beginning of the 20th century.

View attachment 139688

Hearing the Pomp and Circumstance March Number 1, for the first two minutes, it sounds like a nice military march for brass, nothing special. And then, Elgar hits you with what he called, his once-in-a-lifetime melody that would have made Mozart cringe with envy. It’s a heartfelt sweeping melody that brought a mighty nation to its knees. Elgar later rescored it with words for his Land of Hope and Glory, which became the unofficial British national anthem, much like Verdi’s famous Va Pensiero in his opera Nabucco. Telarc received much criticism for its hedonistic recordings of the bass drum, but here the sinful excesses are deeply enjoyable. One senses how a nation was stirred. Music can move people more than armies can. This recording tells you why.The Brits were a cocky bunch at the end of the 19th century. They ruled over an empire where the sun never set. They were the master of the high seas with an unmatched naval force. Their scientists from Isaac Newton to Charles Darwin to Maxwell dominated science. Their steam engines and railroads were the envy of all. Michael Faraday invented electricity. What’s not to like?

For all their prowess, they had one glaring concern. They longed for a composer who could command adulation like Beethoven. All hope seemed lost till salvation arrived in the form of Elgar. His Enigma Variations set the English musical world ablaze. But where was his symphony? They waited and waited. And waited. Finally Elgar delivered his Symphony No 1. And it was a whopper. Finally a symphony made in Britian that could compare with Beethoven and Brahms.

This magisterial recording from Telarc in its golden years under Jack Renner’s recording brilliance shows what a great symphony it was. Elgar hit a home run when he needed to. A nation yearning for musical salvation found its prayers answered. His Pomp and Circumstance march further sealed his reputation as England’s finest composer. When the Pomp and Circumstance march was first performed live, the audience was so enraptured they demanded an encore. The orchestra complied to only be forced to do yet another one. The conductor remarked that it became a complete nuisance as the concert could not continue with other pieces. And so it has become the mainstay of the legendary BBC Proms each year at Covent Garden, which would be unthinkable without a roaring performance of the Pomp and Circumstance March at the end of each season complete with the standing audience adding their dance movements.

This glorious recording shows that even humble 16-bit audio is more than sufficient to reproduce the dynamics of an orchestra with stunning bass drum impact and the golden sound of brass. Telarc never matched the heights they reached in their early years under Jack Renner and his simple three point microphones as they sadly succumbed to the temptations of massive multimiking in later years.

On the big SL’s, the orchestra sounds majestic and commanding. The bass drum is powerful but not subwoofer bloated. It’s fast and the transient hits you and it’s gone within a few hundred milliseconds. Like in a concert hall, you are not left with that slow dynamic loudspeaker box bass response which lingers on like a bad hangover.

Great way to listen to why Elgar was so revered in Britain at the beginning of the 20th century.

View attachment 139688

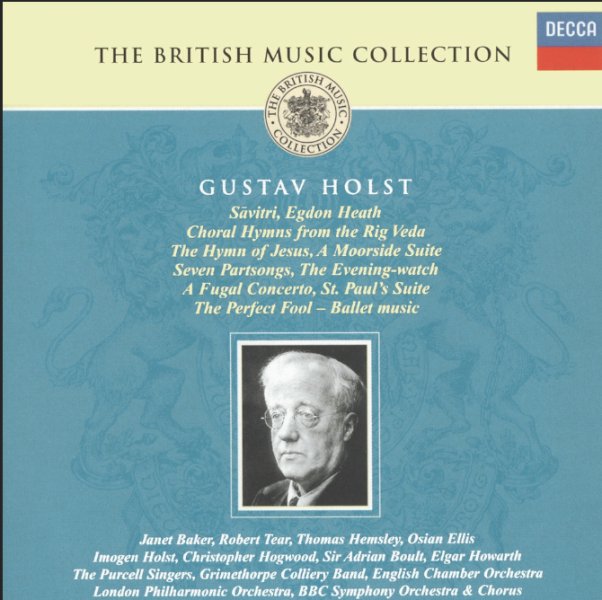

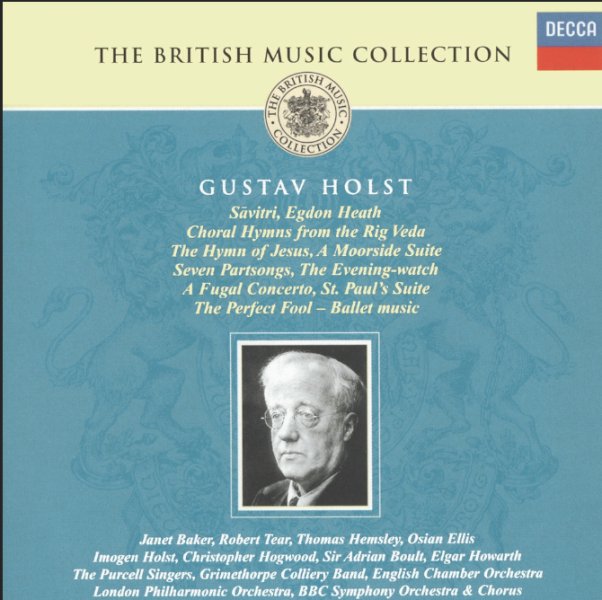

For our last performance of the evening, staying in the British Isles, we move from Lord Elgar, beloved by the King and the royalty, to a humble schoolteacher who erected a soundproof room in his school so that he might compose in his spare time. Which school teacher has any spare time? I speak of course of Gustav Holst, the great composer of The Planets, favorite demonstration disc of none other than the Lord Priest of High End Audio in the 80’s and 90’s, Harry Pearson. Woe befall a manufacturer whose preamplifier or loudspeaker did not do justice to HP’s legendary Super Disc List, one of which was Zubin Mehta’s legendary performance with the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra of The Planets, especially Jupiter, The Bringer of Jollity, on the Decca SXL LP. The rich strings of Jupiter on the last band of Side 1 could bring even a jaded audiophile to tears.

Unlike HP, I’m going with a far more beautiful piece of music by Holst, who loved the sound of oriental music. He wrote a set of Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda, possibly the oldest Indian religious text that’s come down to us from 1500 BC. This lovely Decca recording was conducted by none other than his daughter, Imogen Holst. Like his somewhat contemporaneous physicist Robert Oppenheimer, Holst learned Sanskrit so he could read the original Indian text. Oppenheimer, leader of the Manhattan Project, learned Sanskrit, so he could read the Bhagwad Gita, which he quoted when the first atom bomb was detonated in a New Mexico desert: “Now I have become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds”.

The second piece on this compilation is Holst’s one act chamber opera, Savitri, another ancient story from The Mahabharata, a great Indian mythological story that combines The Game of Thrones with The Ring and then some. Savitri is the wife of a humble woodcutter whose husband Death has come to claim.

Throughout the arts, one finds artists struggle to model Death. Ingmar Bergman, the legendary Swedish filmmaker, modeled Death as an opponent in a game of chess played by a Knight during The Plague in his famous movie The Seventh Seal.

Hearing this riveting piece, I’m reminded of the great American poet Emily Dickinson whose house in Amherst, Massachusetts, I have visited many times when I taught there. Dickinson spent her life in her charming house writing short poems, like this one on Death.

“I had no time for Death, so Death found time for me.

The carriage held but the two of us and eternity”

Hearing Savitri plead with Death frantically for her husband’s life, one wonders which of us would be able to summon such courage. Here’s the full synopsis of the short opera. This is an old analog recording but sounds quite amazing given its age. Decca analog engineering at its finest. The voices are very compelling on the big SL’s with full dynamics without any compression.

Sāvitri, wife of the woodman Satyavān, hears the voice of Death calling to her. He has come to claim her husband. Satyavān arrives to find his wife in distress, but assures Sāvitri that her fears are but Māyā (illusion): "All is unreal, all is Māyā." Even so, at the arrival of Death, all strength leaves him and he falls to the ground. Sāvitri, now alone and desolate, welcomes Death. The latter, moved to compassion by her greeting, offers her a boon of anything but the return of Satyavān. Sāvitri asks for life in all its fullness. After Death grants her request, she informs him that such a life is impossible without Satyavān. Death, defeated, leaves her. Satyavān awakens. Even "Death is Māyā".

Unlike HP, I’m going with a far more beautiful piece of music by Holst, who loved the sound of oriental music. He wrote a set of Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda, possibly the oldest Indian religious text that’s come down to us from 1500 BC. This lovely Decca recording was conducted by none other than his daughter, Imogen Holst. Like his somewhat contemporaneous physicist Robert Oppenheimer, Holst learned Sanskrit so he could read the original Indian text. Oppenheimer, leader of the Manhattan Project, learned Sanskrit, so he could read the Bhagwad Gita, which he quoted when the first atom bomb was detonated in a New Mexico desert: “Now I have become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds”.

The second piece on this compilation is Holst’s one act chamber opera, Savitri, another ancient story from The Mahabharata, a great Indian mythological story that combines The Game of Thrones with The Ring and then some. Savitri is the wife of a humble woodcutter whose husband Death has come to claim.

Throughout the arts, one finds artists struggle to model Death. Ingmar Bergman, the legendary Swedish filmmaker, modeled Death as an opponent in a game of chess played by a Knight during The Plague in his famous movie The Seventh Seal.

Hearing this riveting piece, I’m reminded of the great American poet Emily Dickinson whose house in Amherst, Massachusetts, I have visited many times when I taught there. Dickinson spent her life in her charming house writing short poems, like this one on Death.

“I had no time for Death, so Death found time for me.

The carriage held but the two of us and eternity”

Hearing Savitri plead with Death frantically for her husband’s life, one wonders which of us would be able to summon such courage. Here’s the full synopsis of the short opera. This is an old analog recording but sounds quite amazing given its age. Decca analog engineering at its finest. The voices are very compelling on the big SL’s with full dynamics without any compression.

Sāvitri, wife of the woodman Satyavān, hears the voice of Death calling to her. He has come to claim her husband. Satyavān arrives to find his wife in distress, but assures Sāvitri that her fears are but Māyā (illusion): "All is unreal, all is Māyā." Even so, at the arrival of Death, all strength leaves him and he falls to the ground. Sāvitri, now alone and desolate, welcomes Death. The latter, moved to compassion by her greeting, offers her a boon of anything but the return of Satyavān. Sāvitri asks for life in all its fullness. After Death grants her request, she informs him that such a life is impossible without Satyavān. Death, defeated, leaves her. Satyavān awakens. Even "Death is Māyā".

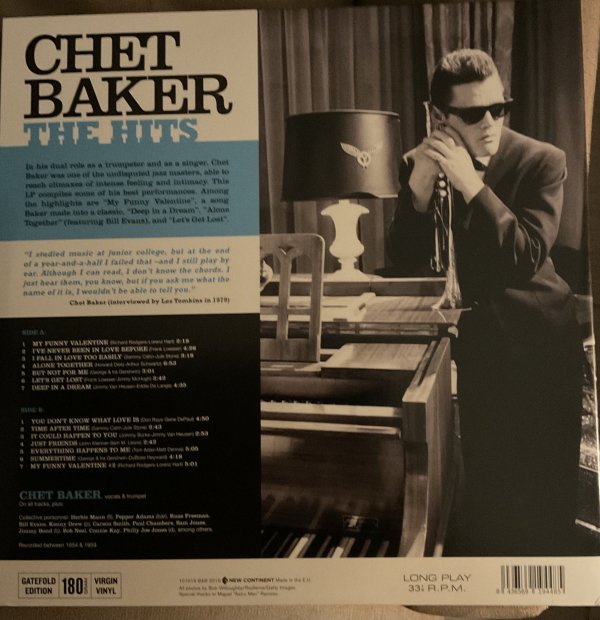

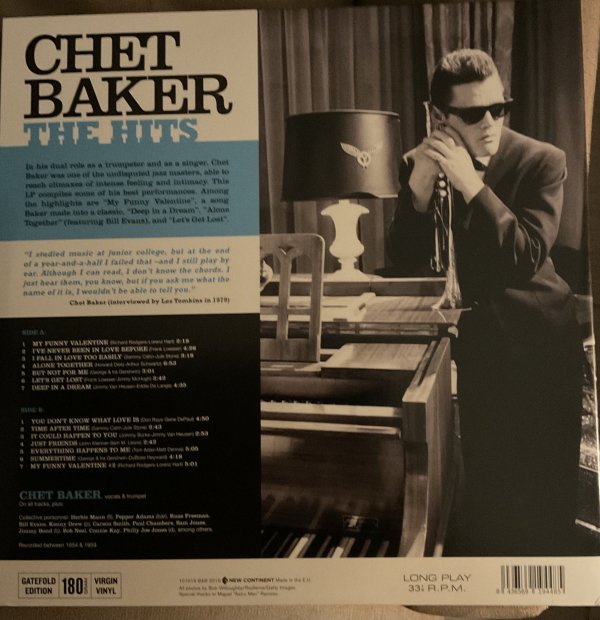

Here’s a lovely Chet Baker album compilation of his greatest hits from the 1950s. Recorded mostly in mono, but sounds incredible. The big SL’s recreate the mono recording as a tight central image, but with plenty of body giving his voice sufficient heft. Played back on my diminutive Technics SL-10 linear tracker into the Mola Mola MAKUA preamp’s phono stage with a Shure V15LT, a P-mount version of the famous V15.

Erik Satie actually was originally Eric Satie, and in a fit of characteristic boldness, replaced the “c” with a “k”. He was born in Normandy on the French coast, from where Britain was visible across the English channel. His mother was British. He entered the conservatoire in Paris, where he was adjudged a lazy student and headstrong. Lifelong friends with Debussy, his music was quite different. This beautiful album of his piano music begins with his most well known Gymnopedies. By way of explanation, the Greek root “gymnos” means naked. And these piano pieces definitely sound that way. Extremely slow tempos with very limited chords, yet they sound enchanting. They have been used in innumerable films and advertisements, so it’s a good chance you already have heard them. It’s a piece that even an amateur feels like playing. A closely miked recording in the usual tradition, but sounds full balanced and warm on the big SL panels. Satie’s music, like his French compatriot Poulenc, was quirky and distinctive, unlike the “Swiss watchmaker”, Maurice Ravel, whose exquisite orchestrations had Stravinsky to make him sound like a well-designed chronograph. Satie was a master of slow tempos, but boy he could bring out so much melody and depth from a few chords played slowly. Even though Chopin lived in Paris, there’s no mistaking one for the other. Satie hung out with artistic royalty. Pablo Picasso commissioned him to write music for his ballet Parade, which caused a minor scandal. What a city to have lived in the early part of the 20th century.

Listen to his Gnossiennes, first movement. What a hauntingly beautiful melody with such a few notes. Listening to this piece makes you want to learn to play the piano. And unlike the really complex chords that Beethoven liked to throw around in his sonatas, Satie showed the virtues of simplicity. As the saying goes, brevity is the soul of wit. Satie’s music certainly has plenty of wit and charm.

Listen to his Gnossiennes, first movement. What a hauntingly beautiful melody with such a few notes. Listening to this piece makes you want to learn to play the piano. And unlike the really complex chords that Beethoven liked to throw around in his sonatas, Satie showed the virtues of simplicity. As the saying goes, brevity is the soul of wit. Satie’s music certainly has plenty of wit and charm.

Last edited:

It seems appropriate to turn from Satie to the beautiful Lyric Pieces by Edward Grieg, here played by the legendary Russian pianist Emil Gilels. I had the original vinyl album that I wore out after too much playing. This is a high resolution 24-bit 96khz remastering from DG. Grieg received his musical education in Leipzig and was greatly influenced by the music of Robert Schumann. His lyric pieces bear striking similarities to Satie’s music. Their tempos are often slow, quiet and meditative. Grieg whose famous Peer Gynt is often heard in concert halls was a great composer in other mediums than tone poems. He shows a very different side to him in these quieter pieces. Gilels bestows all his love in playing these pieces which demand no great pianistic showmanship. Yet Gilels reveals there’s great depth here in these humble pieces.

What makes a great pianist? The legendary pianist Artur Schnabel once said that he played the notes like anyone else. But, ah, he said, the silence between the notes, that’s where the magic lay. Gilels shows us in his deliberate pauses between notes why Schnabel was right. It’s not just the notes that makes music. It’s the gaps, the hesitancy, the pauses, where anticipation builds up for the next note. Play it too quickly and the surprise is lost. Too slow and it sounds boring. The trick is finding the right pauses. The remastered DG recording sounds splendid on the big SL’s, warm and rich, with the great pianist showing consummate skill and artistry in playing pieces that must have seemed a cakewalk for his level of playing. Yet he treats each piece with great care.

What makes a great pianist? The legendary pianist Artur Schnabel once said that he played the notes like anyone else. But, ah, he said, the silence between the notes, that’s where the magic lay. Gilels shows us in his deliberate pauses between notes why Schnabel was right. It’s not just the notes that makes music. It’s the gaps, the hesitancy, the pauses, where anticipation builds up for the next note. Play it too quickly and the surprise is lost. Too slow and it sounds boring. The trick is finding the right pauses. The remastered DG recording sounds splendid on the big SL’s, warm and rich, with the great pianist showing consummate skill and artistry in playing pieces that must have seemed a cakewalk for his level of playing. Yet he treats each piece with great care.

Claudio Monteverdi was a 17th century Italian composer who wrote much magnificent music. One of his major compositions is Selva Morale e Spirituale, meaning Moral and Spiritual Forest, a collection of sacred music for voices and instruments, here recorded in its entirety on a magnificent Harmonia Mundi album. This work, almost 4 hours long, was published in Venice in 1640, almost 400 years ago, but it sounds so beautiful that it puts to shame many later compositions even from this or the previous centuries. Whatever the benefits science and technology have yielded, they don’t a better composer make. Whatever use is technology to a composer who must use his creative powers to write music? Whatever use is knowing the laws of physics or economics or the fact that genes are encoded as strands of DNA in a double helix? Something to ponder. Which modern composer can compare to Bach, Beethoven or Mozart or Monteverdi? None I wager. The age of greatness in classical music is over. Now all we have are recordings.

This recording is 16-bit, but that’s largely immaterial as I have long ago realized but depth has nothing to do with recording quality. On the big SL’s, the voices sound full and natural with no brightness. The original instruments are also nicely captured. The recording is a bit more closely miked than is perhaps appropriate but it puts you in the center of action. Many years ago when I visited Venice, I had the pleasure of hearing choral music in churches, which was an unforgettable experience. Vivaldi set up shop in Venice, which was then a center of artistic and business, much as Vienna would become later. Venice is a floating city that is slowly sinking, although great efforts are being made to save the city. It’s sadly the victim of over tourism, but now large cruise ships are banned from docking there, which should help a bit. I wonder what Monteverdi would make of his city if he should visit it now.

This recording is 16-bit, but that’s largely immaterial as I have long ago realized but depth has nothing to do with recording quality. On the big SL’s, the voices sound full and natural with no brightness. The original instruments are also nicely captured. The recording is a bit more closely miked than is perhaps appropriate but it puts you in the center of action. Many years ago when I visited Venice, I had the pleasure of hearing choral music in churches, which was an unforgettable experience. Vivaldi set up shop in Venice, which was then a center of artistic and business, much as Vienna would become later. Venice is a floating city that is slowly sinking, although great efforts are being made to save the city. It’s sadly the victim of over tourism, but now large cruise ships are banned from docking there, which should help a bit. I wonder what Monteverdi would make of his city if he should visit it now.

Is there anything left to say or record about Mozart’s symphonies? They’ve been performed and recorded ad nauseam for over a hundred years with countless versions to choose from. Here we have a modern DSD recording from Linn, the legendary Scottish turntable maker, with Sir Charles Mackerras and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. Mackerras was almost 80 when he recorded these. 30 years ago, he recorded the symphonies for Telarc with the Prague Chamber Orchestra. In every way, I prefer the earlier version ever though that was a humble red book CD at 16-bit depth. It was a warmer more musical performance recorded by the legendary Jack Renner using a simple three tube microphone setup. This new version is much brighter, and sounds like it’s been multimiked. The performance is slower and more deliberate. There’s much to enjoy here. Mackerras was a great conductor and the SCO play their hearts out for him. I can’t help but wonder if the period instrument movement had their deleterious effect here with the orchestra trying to sound like The Academy of Ancient Music. No matter, Mozart is ultimately Mozart, and his genius shines through what would be his last set of symphonies.

The strings are brightly lit on the big SL’s and the brass has a bite to it. But overall the music making is infectious. It’s sad to think of Mozart’s last days and him being buried in a pauper’s grave. Surely he deserved better.

The strings are brightly lit on the big SL’s and the brass has a bite to it. But overall the music making is infectious. It’s sad to think of Mozart’s last days and him being buried in a pauper’s grave. Surely he deserved better.

And we end with Vivaldi, in particular his Gloria composed in 1715 in Venice, 75 years after Monteverdi’s Selva Morale e Spirituale. Once upon a time many years ago I knew Vivaldi primarily as a composer of The Four Seasons, a warhorse that has been popularized beyond imagination, but his greatest compositions are for voice. This recording by King is part of a series featuring all of Vivaldi’s sacred music and sounds splendid on the big SL’s. The chorus is warm and full sounding and the strings are a bit acerbic but that’s appropriate in an original instrument recording. The music itself is vintage Vivaldi. The melody is full of bounce and verve and is sure to cheer anyone on a dreary cold weekend, as we are having in the Bay Area where the temperature tomorrow morning is around 36 degrees Fahrenheit. Where did the fall go? Winter is here, and with it, of course, Handel, Vivaldi, and the familiar standard bearers of holiday music. Innumerable performances of The Messiah will no doubt occur. But one of this should detract from the glory of Vivaldi’s Gloria. Just listen to the opening oboe piece in the Domine Deus movement. It will melt your heart.

This delightful album of Mendelssohn’s music for cello made many best recordings of 2024 lists for good reasons. It’s beautifully played and although the instruments are a bit closely miked, sounds great on the big SL’s. Mendelssohn was as great a child prodigy as Mozart and had a huge advantage of growing up in a highly affluent home in Berlin, whose salon concerts were attended by the cream of 19th century German intellectuals, from artists to writers to scientists that reads like a Who’s Who list today. Unlike Mozart who was forced to scrape together a living, never easy when you are brash and opinionated, Mendelssohn had a loving family that supported him and he never wanted for money. It’s remarkable that given this level of privilege he produced music of such precocity and genius. A popular view of great art is that the artist must suffer: Beethoven’s deafness at the height of his creative powers, Vincent Van Gogh peddling his paintings in French cafes for a few francs that now routinely sell for hundreds of millions of dollars, and Schubert struggling to survive helped by his friends. Mendelssohn didn’t need for anything and yet he achieved greatness in music helped by an astonishing talent that was carefully nurtured by his parents. Cellists are in love with Mendelssohn for the riches he left behind fir their instrument. This recording shows why the cello remains the instrument closest to the human voice in expressiveness.

A

A

Like certain kinds of dark German beer, Bruckner seems like an acquired taste. I much prefer the symphonies of Mahler, if I wanted to listen to a 20th century composer. Bruckner’ choral music, his motets and masses, I find far more pleasurable. His symphonies are overly long, filled with massive granite walls of sound, huge amounts of brass, and little by way of genuine melody. But I suppose if I heard Bruckner everyday for a year, I could grow to like his symphonies. This recording of his 8th is very well done for a studio recording and the brass sounds full and warm on the big SL’s. The strings are natural and not bright. Jaap van Zweden’s reading won’t sway those who like the great Bruckner conductors like Eugene Jochum or even Herbert von Karajan. The NRPO is not the Vienna Philharmonic, where Bruckner’s 8th was originally performed in 1892 at the Musikverein by conductor Hans Richter. The eight was his last symphony and like many of his symphonies, extensively revised and comes in multiple versions. Bruckner dedicated the symphony to Emperor Franz Joseph I, who agreed to pay for its publication costs.

The story behind the inaugural performance is worth quoting from Wikipedia. It had its critics, as with all his symphonies, but over time, it has taken a center stage among the great symphonies of the 20th century.

After a Munich performance by Levi was cancelled because of a feared outbreak of cholera, Bruckner focused his efforts on securing a Vienna premiere for the symphony. At last Hans Richter, subscription conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic, agreed to conduct the work. The first performance took place on 18 December 1892. Although some of the more conservative members of the audience left at the end of each movement, many of Bruckner's supporters were also present, including Hugo Wolf and Johann Strauss.

The well known critic Eduard Hanslick left after the slow movement. His review described the symphony as "interesting in detail, but strange as a whole, indeed repellent. The peculiarity of this work consists, to put it briefly, in importing Wagner's dramatic style into the symphony." (Korstvedt points out that this was less negative than Hanslick's reviews of Bruckner's earlier symphonies.) There were also many positive reviews from Bruckner's admirers. One anonymous writer described the symphony as "the crown of music in our time". Hugo Wolf wrote to a friend that the symphony was "the work of a giant" that "surpasses the other symphonies of the master in intellectual scope, awesomeness, and greatness".

The story behind the inaugural performance is worth quoting from Wikipedia. It had its critics, as with all his symphonies, but over time, it has taken a center stage among the great symphonies of the 20th century.

After a Munich performance by Levi was cancelled because of a feared outbreak of cholera, Bruckner focused his efforts on securing a Vienna premiere for the symphony. At last Hans Richter, subscription conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic, agreed to conduct the work. The first performance took place on 18 December 1892. Although some of the more conservative members of the audience left at the end of each movement, many of Bruckner's supporters were also present, including Hugo Wolf and Johann Strauss.

The well known critic Eduard Hanslick left after the slow movement. His review described the symphony as "interesting in detail, but strange as a whole, indeed repellent. The peculiarity of this work consists, to put it briefly, in importing Wagner's dramatic style into the symphony." (Korstvedt points out that this was less negative than Hanslick's reviews of Bruckner's earlier symphonies.) There were also many positive reviews from Bruckner's admirers. One anonymous writer described the symphony as "the crown of music in our time". Hugo Wolf wrote to a friend that the symphony was "the work of a giant" that "surpasses the other symphonies of the master in intellectual scope, awesomeness, and greatness".

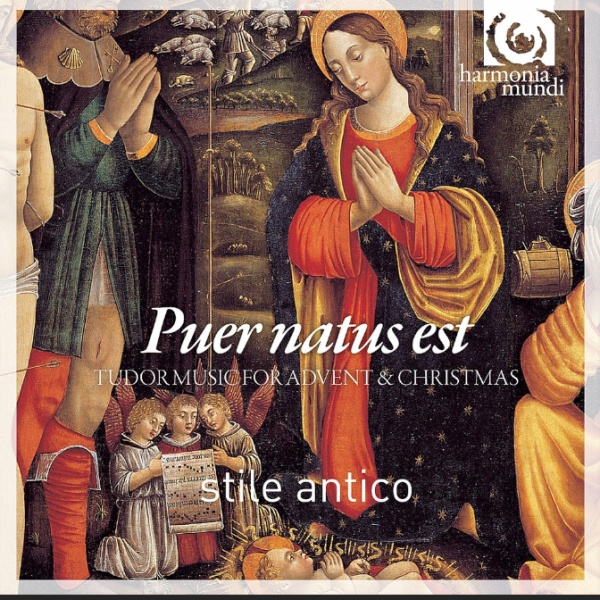

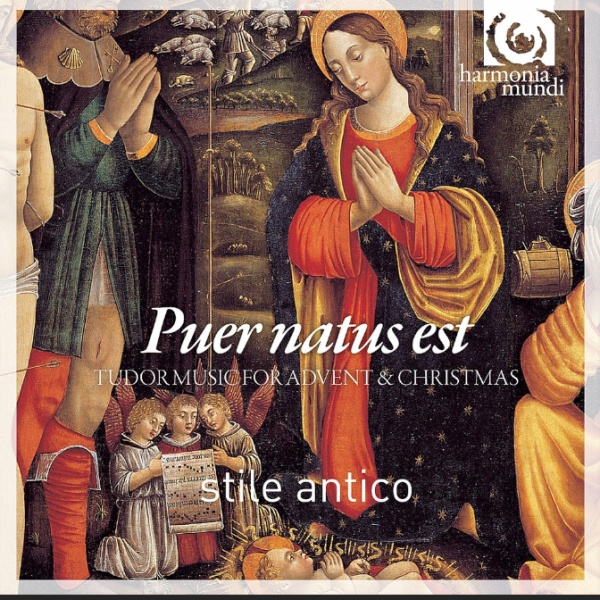

After 80-odd minutes of hearing roaring brass from Bruckner, I feel like I need time off for good behavior. Salvation comes from this lovely album of English Renaissance music from one of my favorite groups, Stile Antico, recorded splendidly as always by Harmonia Mundi. Appropriate music for the upcoming holiday season. I find the human voice the toughest test for any loudspeaker and most audiophile loudspeakers fall flat on their face trying to reproduce the one sound we all know better than any other sound. The big SL’s ace this test sounding splendid on this beautiful recording with the voices sounding like they would in the real world with not a hint of brightness or stridency or glare. Listening to this recording is like basking in the warm afternoon sun on the cold winter days that are approaching. Highly recommended as a microscope to take apart any audiophile loudspeaker and to enjoy just the sound of human voices, the greatest musical instrument ever devised.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 777

- Replies

- 4

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 10

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 4

- Views

- 519

| Steve Williams Site Founder | Site Owner | Administrator | Ron Resnick Site Owner | Administrator | Julian (The Fixer) Website Build | Marketing Managersing |