Is ABX finally Obsolete

- Thread starter Gregadd

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

This is a touchy subject but this is the place.

What seems lost in that article is the “other side” of the argument and cite tests where people concluded various types of equipment sounded the same as proof the test doesn’t work.

It only means in those tests, there was no conclusive result. I have participated in a rigorous ABX test and could hear and identify some differences between amplifiers bfd.

The other side is the high degree ones sense are all tied together and based on what you already know. I know this sounds hard to accept but recent discoveries on our senses are shedding more and more light on the subject of this interconnectedness and prior knowledge.

A cool show was on the science channel the other night "to see or not to see" which dealt with the senses.

An example is below, think your ears and senses are infallible, that your ears are not affected by what you see and expect?, try this test and see.

http://www.wimp.com/mcgurkeffect/

The usefulness of this and lets call it “testing without prior knowledge” is that it removes what you know about the object under test.

There are examples of testing without prior knowledge all around us.

For example, when you do a vision test, you try to read smaller and smaller letters.

Notice WORDS are NOT used even though you read words, the reason is they want to remove any “prior knowledge” and if you used words, peoples vision (because of the ability to guess the letters) is greatly improved compared to random letters which depends entirely on making out each letter individually reflecting only ones visual acuity.

In a hearing test, one sits and signals when you hear the sound. There is no red light that goes on, there is no visual contact with the person running the test, there are no clues to the presence or absence of the test tone, you must depend only what your ears alone can tell you. If there was a visual signal too, like a red light coming on each time, like the tester winking at you, the test results are much better, better because they included more than just your hearing alone.

In commercial sound, there is a similar test, intelligibility. A series of random words (usually 200) are used, the score depends on how many words you could make out correctly. Here It doesn’t matter how “realistic” or natural sounding the words are if you can’t hear what word it is. Here it doesn’t matter what you know about the speaker or what you can see, only what you can hear governs the ineligibility.

Interestingly, unlike intelligibility, one could argue that since one has no idea what the original performance sounded like from the mic positions, or how the recording was mastered and shaped into stereo, that this is sort of a vision test where both you and the doctor have no idea what’s on the test card. It is a judgment based entirely on your knowledge and expectation of what it should sound like. In the extreme case of subjective error, a very natural voice sounding reverberant field conveys no intelligible information.

With the McGurke effect, one hears the sound correctly when one’s eyes are closed but when the eyes are open, you hear only what corresponds to what you see.

While the scientific rigor needed to do medical or other full out scientific testing is high, the usefulness of it can be realized at a much simpler level.

For the curious, what you need is a way to quickly / instantly switch between A and B and not know which was which.

One does the test when you feel like it, not under pressure or hurried. You do it on your own equipment in your own room at your leisure.

I found that searching through recordings to find passages that “brought out” differences and then using these when switching back and forth was most useful.

In auditioning amplifiers for example, it was interesting that the formerly large audible differences some “heard” going into it, were often greatly reduced greatly when the amp in question was “unknown” and did not return when switching back to the known condition and this was emotionally distressing for some.

For that reason, I wouldn’t suggest doing these kinds of tests in the home unless one is prepared to possibly lose some of the ”magic” part. But if you’re doing product engineering and want to hear the actual differences limited to the sound reaching your ears, then this can be useful weeding out differences especially when it involves a great deal of money (like which crossover parts to use).

If you really can’t hear the difference between A and B, even with the most revealing recordings, how valuable is this change?

If you could clearly hear a big difference before the test but smaller or not at all after, what does that tell you about what you were hearing before?

If you can still hear a difference without prior knowledge, was there any harm or risk in simply trying the test?

Sure one can do the test incorrectly or in a biased way or argue that the end user doesn’t need to or even shouldn’t separate these things, but this doesn’t change the fact that when they test just one of your senses, this IS how it’s done.

When an audio evaluation is limited to just the vibrating airborne sound entering ones ears you also get more accurate results when you eliminate the other non-acoustic inputs.

Best,

Tom Danley

Danley Sound Labs

What seems lost in that article is the “other side” of the argument and cite tests where people concluded various types of equipment sounded the same as proof the test doesn’t work.

It only means in those tests, there was no conclusive result. I have participated in a rigorous ABX test and could hear and identify some differences between amplifiers bfd.

The other side is the high degree ones sense are all tied together and based on what you already know. I know this sounds hard to accept but recent discoveries on our senses are shedding more and more light on the subject of this interconnectedness and prior knowledge.

A cool show was on the science channel the other night "to see or not to see" which dealt with the senses.

An example is below, think your ears and senses are infallible, that your ears are not affected by what you see and expect?, try this test and see.

http://www.wimp.com/mcgurkeffect/

The usefulness of this and lets call it “testing without prior knowledge” is that it removes what you know about the object under test.

There are examples of testing without prior knowledge all around us.

For example, when you do a vision test, you try to read smaller and smaller letters.

Notice WORDS are NOT used even though you read words, the reason is they want to remove any “prior knowledge” and if you used words, peoples vision (because of the ability to guess the letters) is greatly improved compared to random letters which depends entirely on making out each letter individually reflecting only ones visual acuity.

In a hearing test, one sits and signals when you hear the sound. There is no red light that goes on, there is no visual contact with the person running the test, there are no clues to the presence or absence of the test tone, you must depend only what your ears alone can tell you. If there was a visual signal too, like a red light coming on each time, like the tester winking at you, the test results are much better, better because they included more than just your hearing alone.

In commercial sound, there is a similar test, intelligibility. A series of random words (usually 200) are used, the score depends on how many words you could make out correctly. Here It doesn’t matter how “realistic” or natural sounding the words are if you can’t hear what word it is. Here it doesn’t matter what you know about the speaker or what you can see, only what you can hear governs the ineligibility.

Interestingly, unlike intelligibility, one could argue that since one has no idea what the original performance sounded like from the mic positions, or how the recording was mastered and shaped into stereo, that this is sort of a vision test where both you and the doctor have no idea what’s on the test card. It is a judgment based entirely on your knowledge and expectation of what it should sound like. In the extreme case of subjective error, a very natural voice sounding reverberant field conveys no intelligible information.

With the McGurke effect, one hears the sound correctly when one’s eyes are closed but when the eyes are open, you hear only what corresponds to what you see.

While the scientific rigor needed to do medical or other full out scientific testing is high, the usefulness of it can be realized at a much simpler level.

For the curious, what you need is a way to quickly / instantly switch between A and B and not know which was which.

One does the test when you feel like it, not under pressure or hurried. You do it on your own equipment in your own room at your leisure.

I found that searching through recordings to find passages that “brought out” differences and then using these when switching back and forth was most useful.

In auditioning amplifiers for example, it was interesting that the formerly large audible differences some “heard” going into it, were often greatly reduced greatly when the amp in question was “unknown” and did not return when switching back to the known condition and this was emotionally distressing for some.

For that reason, I wouldn’t suggest doing these kinds of tests in the home unless one is prepared to possibly lose some of the ”magic” part. But if you’re doing product engineering and want to hear the actual differences limited to the sound reaching your ears, then this can be useful weeding out differences especially when it involves a great deal of money (like which crossover parts to use).

If you really can’t hear the difference between A and B, even with the most revealing recordings, how valuable is this change?

If you could clearly hear a big difference before the test but smaller or not at all after, what does that tell you about what you were hearing before?

If you can still hear a difference without prior knowledge, was there any harm or risk in simply trying the test?

Sure one can do the test incorrectly or in a biased way or argue that the end user doesn’t need to or even shouldn’t separate these things, but this doesn’t change the fact that when they test just one of your senses, this IS how it’s done.

When an audio evaluation is limited to just the vibrating airborne sound entering ones ears you also get more accurate results when you eliminate the other non-acoustic inputs.

Best,

Tom Danley

Danley Sound Labs

Arny, we do not tolerate personal remarks like this. Most members use aliases including many people you don't complain about. Please refrain from such language.The above exception to Toole's viewpoint is stated as an excluded middle argument. If taken at face value it appears to be just another transparent ploy by a highly biased unknown individual who hides behind an alias to discredit a great man, an industry leader, and a great scientist.

(...)

Where in the above comments from Floyd Toole above was "he was just stating that differences between electronics are very small."?

Just to answer your question

"ABX testing is just one of many techniques for evaluating sound quality. It is very useful for settling "is there an audible difference" kinds of tests - e.g. wires, CD players, amplifiers, perceptual encoders. The results of such tests are, ideally, yes or no. For loudspeakers, the differences are clearly audible, and the question is more one of preference and why there is a preference, so we use multiple comparison techniques, which give listeners a better "context" within which to form what is a very complicated opinion."

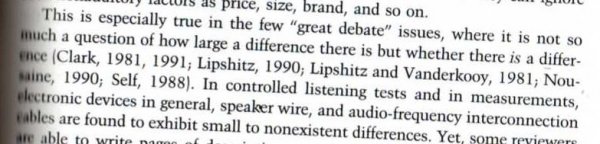

My interpretation is that when Toole contrasts "wires, CD players, amplifiers, perceptual encoders" versus "loudspeakers" stating that in the last case differences were clearly audible he is scaling the differences. Anyway my interpretation of his view was supported by later writings in "Sound Reproduction" as quoted below.

Attachments

...and ABX full of false negatives See, proving the null hypothesis.

Are you saying that it can be, or always is?

My interpretation is that when Toole contrasts "wires, CD players, amplifiers, perceptual encoders" versus "loudspeakers" stating that in the last case differences were clearly audible he is scaling the differences. Anyway my interpretation of his view was supported by later writings in "Sound Reproduction" as quoted below.

You said and I quote exactly:

"F. Toole is known for his position of stating that all electronics sounds the same - it is not an unbiased view."

You have now quoted Toole as saying:

"In controlled listening tests, and in measurements, electronic devices in general, speaker wire and audio frequency interconnection devices are found to exhibit small to non-existent diferences."

I agree with you that the viewpoint: "all electronics sounds the same" would be a biased viewpoint, but I can't see any way that this is what Toole said.

You statement as I quoted it above does not seem to be about shades of grey or "scaled differences".

Did you not say with no qualifications whatsoever that it was Toole's belief that all electronics sounds the same?

There is a link above. To prove the null hypothesis you would like to to see at least 1/20. Howevever the quest is to look for a result that is inconsistent with guessing. Getting one 1/20 suggest you are keying in on somehting. Morevoer while 10/20 is consitent with guessing, it also consitent with correctly identifyng 10/20.

(...) Did you not say with no qualifications whatsoever that it was Toole's belief that all electronics sounds the same?

It was evidently a typing mistake that I corrected as soon as possible in next postings . You were faster to take advantage of such an overstatement. Sometimes mind goes faster than fingers ... See post #253

"Ok, I hope everyone of you will be pleased "Every competently designed electronics will sound the same", "differences between correctly designed electronics are small" . I missed the "competently designed" when I typed the post with the quote from the Toole book. "

(before I go on,now that I am replying, Greg, heard you earlier about my 'language', got you. Thanks)

Tom, wow! What a fantastic idea for a test disc! Or better still, some sort of computer program?

If you don't mind (because your long posts are very bit as useful and entertaining as Arts, so thanks for them)...when you do this test is it just the words alone, or over the top/buried in music. This is done during you speaker development, or at gigs and such?

Steroeophile should commission a disc like this, along with all the other stuff they do (who wants yet another disk with pink noise!? haha), well here is a fantastic real world test disc.

haha), well here is a fantastic real world test disc.

The downside is that word would get around what the words are (ie no longer 'random')...but hey that is always an excuse for disc two no? (which is why if it could be done a computer program always inserting new words or changing the order may have longer longevity)

(which is why if it could be done a computer program always inserting new words or changing the order may have longer longevity)

Play the disc, and see how many of these random words in the music you hear, voila, an accurate rankable indication of the resolution. Hah, change the toe in or out, see if it helps, closer/further to the walls etc.

Hey, maybe there is a new market for you Tom? The Danley Sounds intelligibility test disc?

Anyway, no-one else commented, but it just JUMPED out at me for some reason!

In commercial sound, there is a similar test, intelligibility. A series of random words (usually 200) are used, the score depends on how many words you could make out correctly. Here It doesn’t matter how “realistic” or natural sounding the words are if you can’t hear what word it is. Here it doesn’t matter what you know about the speaker or what you can see, only what you can hear governs the ineligibility.

Tom Danley

Danley Sound Labs

Tom, wow! What a fantastic idea for a test disc! Or better still, some sort of computer program?

If you don't mind (because your long posts are very bit as useful and entertaining as Arts, so thanks for them)...when you do this test is it just the words alone, or over the top/buried in music. This is done during you speaker development, or at gigs and such?

Steroeophile should commission a disc like this, along with all the other stuff they do (who wants yet another disk with pink noise!?

The downside is that word would get around what the words are (ie no longer 'random')...but hey that is always an excuse for disc two no?

Play the disc, and see how many of these random words in the music you hear, voila, an accurate rankable indication of the resolution. Hah, change the toe in or out, see if it helps, closer/further to the walls etc.

Hey, maybe there is a new market for you Tom? The Danley Sounds intelligibility test disc?

Anyway, no-one else commented, but it just JUMPED out at me for some reason!

I'm curious about the next sentence in that image posted by Micro which begins: "Yet, some reviewers ..."You have now quoted Toole as saying:

"In controlled listening tests, and in measurements, electronic devices in general, speaker wire and audio frequency interconnection devices are found to exhibit small to non-existent diferences."

Steve Williams

Site Founder, Site Co-Owner, Administrator

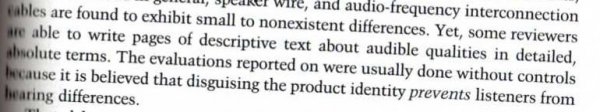

You will be disappointed because it is nothing really new , but I want you all to sleep well tonight:Yet some reviewers are able to write pages of ........

Attachments

So true. Of course, the elephant in the room is how do we go about testing.

That is the "400lb. gorilla in the room." I think we can say blind testing is safe at least for thise who care to indulge.

The problem is there are so many permtuations. Suppoose we have an 18 watt SET trying to drive an Appogee Scintilla. Now let's take Dan A'gositno's new Momentum amp. It doubles down to 1200 watts @ 2ohms. I have not heard it but I think I can produce some source material that will make them sound different. I'll bet my lunch money on that. Extreme example? Yes. That's what happens when you make an absolute statement.

That is the "400lb. gorilla in the room." I think we can say blind testing is safe at least for thise who care to indulge.

The problem is there are so many permtuations. Suppoose we have an 18 watt SET trying to drive an Appogee Scintilla. Now let's take Dan A'gositno's new Momentum amp. It doubles down to 1200 watts @ 2ohms. I have not heard it but I think I can produce some source material that will make them sound different. I'll bet my lunch money on that. Extreme example? Yes. That's what happens when you make an absolute statement.

I've seen that extreme statement here in quotation marks, and attributed to Toole, but I still haven't seen it referenced, in context. Can anyone point me to it? How about providing a scan as has been done for other, less extreme statements from Mr. Toole? Personally, I'd like to judge Mr. Toole by Mr. Toole's statements, in whole, not by what someone said he said.

Oh, and yes, an extreme example. So deliberately and manipulatively extreme that it can't possibly be taken seriously. But no matter. Those of us who believe that competently designed amplifiers operating within their limitations are pretty hard to distinguish from one another pretty much believe that "18 watt SET" and "competently designed amplifier operating within its limitations" is a contradiction of terms.

Tim

Suppoose we have an 18 watt SET trying to drive an Appogee Scintilla. Now let's take Dan A'gositno's new Momentum amp. It doubles down to 1200 watts @ 2ohms. I have not heard it but I think I can produce some source material that will make them sound different. I'll bet my lunch money on that. Extreme example? Yes. That's what happens when you make an absolute statement.

Yep.

As I just remarked elsewhere, you would include Lamm amps in that stereotyping, Tim?Those of us who believe that competently designed amplifiers operating within their limitations are pretty hard to distinguish from one another pretty much believe that "18 watt SET" and "competently designed amplifier operating within its limitations" is a contradiction of terms.

Tim

Frank

As I just remarked elsewhere, you would include Lamm amps in that stereotyping, Tim?

Frank

Does Lamm make an 18 watt SET, Frank? Given the extreme limitations of an 18 watt amp, if they do, yeah, I'd paint the Lamm with that brush. I suppose it depends on what you call "competently designed."

Tim

See http://www.audiofederation.com/blog/archives/787, first one up on Google using "lamm set 18" ...Does Lamm make an 18 watt SET, Frank? Given the extreme limitations of an 18 watt amp, if they do, yeah, I'd paint the Lamm with that brush. I suppose it depends on what you call "competently designed."

Tim

Frank

Steve Williams

Site Founder, Site Co-Owner, Administrator

Does Lamm make an 18 watt SET, Frank? Given the extreme limitations of an 18 watt amp, if they do, yeah, I'd paint the Lamm with that brush. I suppose it depends on what you call "competently designed."

Tim

It's called the ML 2.1 (now the 2.2) which I owned and indeed an 18 wpc SET. It was the second best amp I have ever owned

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 28

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 41

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 239

- Views

- 13K

- Replies

- 9

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 848

| Steve Williams Site Founder | Site Owner | Administrator | Ron Resnick Site Owner | Administrator | Julian (The Fixer) Website Build | Marketing Managersing |