More on gain structuring with the dbx VENU360:

One way to actually improve the signal to noise-plus-distortion ratio of any audio system is to take care of gain structuring. This is not tweaky or controversial in any way. Pro audio systems are usually set up to have proper gain structuring, but most consumer audio set-ups do not easily allow this.

In most cases of consumer audio, proper gain structuring will involve putting a volume control just upstream of your power amplifier, if it doesn't have one built in. Few consumer amps have a volume control on the input, though most pro-audio amps do.

Most consumer amps have far more gain than you need. You can tell whether this is so by testing whatever system volume control you are using. If that volume control will allow you to turn your system up to a far higher SPL than you ever need even with your quietest sources, you could further optimize your system's gain structure by "turning down" the gain of your amplifier. This will also prevent amplifier clipping and speaker damage.

Tube amps are notorious for having very low input sensitivities, usually putting out full power with just 0.775 volts of input. Even transistor amps seldom have input sensitivities above one or two volts. That means that that much voltage will drive them to full output. Standard CD players have an output of 2 volts for the maximum undistorted signal. Many high-end consumer sources, such as preamps, DACs, and streamers, have much hotter signals than that (my Lumin X1 puts out 6 volts max).

By proper gain structuring it's usually possible to add several dB of actual signal to noise and distortion ratio to your system. You can hear this by putting your ear close to the tweeter. Without proper gain structuring, you will frequently hear some hiss without any music playing from within a foot or more of the tweeter at any setting of your system volume control, even the minimum setting. With proper gain structuring, you may hear no hiss, or at least greatly reduced hiss.

One of the things I really like about the dbx VENU360 unit Sanders uses as his (crossover, EQ, time alignment) control unit for the 10e speakers is that it has very flexible levels of input sensitivity and output voltage adjustable in the analog domain through the device's Utility menu. Since this unit directly feeds the Sanders Magtech amps it can act as an input sensitivity control for the amps. The difference in quiescent hiss audible from the stat panels is quite noticeable. As delivered, there was a slight hiss audible, but with proper adjustment, absolutely no hiss is audible at any setting of the system volume control (the Lumin X1's Leedh-processed digital volume control in my case) at any setting of that volume control when no music is playing.

A bit of the theory behind gain structuring and how to do it with the dbx unit are explained on pages 52 - 54 of the

dbx VENU360 manual; note especially the Tip on page 53.

Generally, proper gain structuring relies on lots of gain taken at the initial stages of the sonic chain. Many pro-audio mixers thus have a high maximum output of 18 or 24 dBu, so a consumer audio preamp with a high voltage output makes sense--IF you can decrease the voltage further down the signal chain before the power amp gets hold of it.

The output impedance of most active preamps does not vary with the setting of the preamp's volume control; the output is buffered to have a uniformly low output impedance. Only a so-called passive preamp (rare these days because of potential problems driving cables and downstream equipment) would have a variable output impedance depending on the setting of the volume control.

Any preamp with a constant high output impedance should be rejected out of hand due to difficulty driving cables and downstream equipment. One exception would be if you use low capacitance interconnects and the downstream equipment is designed to have extremely high input impedance, such as a megaohm. A few companies do that to make their equipment as immune as possible from the electrical characteristics of the driving components and cables.

The debate over the worth of an analog preamp in an all-digital system goes on and on. More and more high-end audio manufacturers recommend direct connection of their digitally volume controlled streamers to power amps.

As I recall, the last time I used an analog preamp with more than unity gain available was the first time I had Sanders speakers about a decade ago. I had the Sanders preamp for a short time before I realized its additional gain was totally unnecessary and not otherwise sonically helpful in any way.

However, many audiophiles prefer eliminating the digital volume control in favor of using an analog preamp. Sometimes I think this may come down to the strong preference of most audiophiles for having a system with a lot of excess gain available from the system volume control. Many audiophiles seem to think that their volume controls should be running in the 9 to 11 o'clock region so that there is lots of "reserve" volume. Nothing could be further from the truth, both for analog and digital volume controls in a properly gain-structured system. Both should be run as nearly wide open as possible (assuming doing so does not drive the unit with the volume control into clipping distortion) since both analog pots and digital volume controls at least theoretically will have less effect on the sound toward the top end of their ranges.

Proper gain structuring will result in your system volume control working in the top third of its range for serious listening with most sources. Sources differ wildly as to how "loud" they are and thus you need to allow for enough excess volume control gain to get the maximum SPL you want from your speakers with your quietest sources. Among the quietest sources I've encountered are Sheffield Lab CDs and the signals from a few internet radio stations such as BBC3, WILL, and ABC Jazz.

I find nothing amiss with digital system volume control these days. With the volume processors running at 24 bits resolution as they do, a digital volume control has plenty of volume attenuation available before the signal is meaningfully compromised. In my system, the digital volume control in the Benchmark DAC 3 sounded just fine, only slightly bettered by the use of the downstream HPA4 relay-controlled all-analog volume control. I later found that the Lumin X1's digital volume control also seemed fine sounding--at least as good as running the Lumin with its digital volume control disabled through the Benchmark HPA4. And since then the Lumin volume control has been made yet better sounding with the addition of Leedh digital processing which can be switched in and out for comparison.

Yes, the hierarchy of system set-up is first to buy inherently good sounding speakers (whatever that means to you), then move the speakers and listening position to get the bass response as smooth as possible while also optimizing the spatial aspects of the presentation, then apply room treatment to absorb or diffuse annoying mid- and high-frequency room surface reflections and further optimize the spatial aspects of the presentation, and then use electronic equalization to smooth out the remaining response wrinkles, especially in the bass. No one is disputing that.

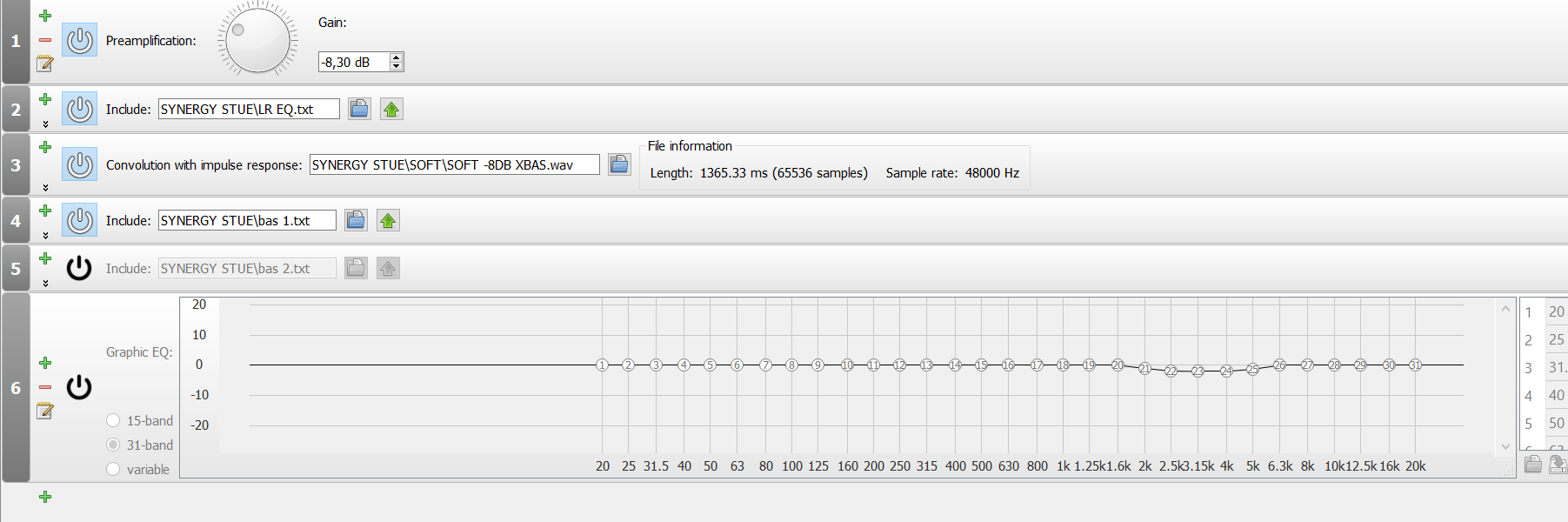

Perhaps this got lost along the way, but the gain structuring I'm talking about is only possible because the dbx VENU360 electronic equalizer I'm currently using, the loudspeaker management system unit that comes with the Sanders 10e speakers, allows such gain structuring.

Unlike any other equalizer I've owned (and I've owned quite a few) it has selectable analog domain input sensitivity and output voltage controls.

If you think gain structuring doesn't matter, that's fine. Think what you want. But pro audio folks have gain structured their recording and playback systems for many decades. If you think increasing the signal to noise and distortion ratio of your system by, say, 12 dB is meaningless, that's your prerogative. Some believe that a signal to noise and distortion ratio of 70 dB is just fine because if the noise is any lower it's inaudible anyway. With digital sources, you certainly don't need gain structuring to reach that level of S/N+D.

Using the dbx unit I'm using as an EQ device makes gain structuring my home audio system very easy. If you are using a pro-audio type of amplifier--most of which have an analog volume control built into their input--it also will be very easy.

But if you are using a typical consumer/audiophile amp with no volume control on its inputs, to properly gain structure your system you would have to add an analog volume control to your amp input. One way to do that is to buy a fixed resistor or variable pot and plug that directly into the amp input and allow your upstream components to feed that. A couple decades ago I owned a pair of variable pots for this purpose. They were called

EVS Ultimate Attenuators. Cheaper and more compact solutions are certainly available, especially if you opt for a fixed resistor control to knock down the voltage going into the amp.