Listening to Loud Sounds: Adaptation, Conditioning, and Acculturation

Listening to possible harmful sounds can be classified as health-risk behavior that accounts for both individual attitudes and beliefs and the impact of aspects of the social environment. The problem of possible harmful effects, however, is difficult to control as the personal rewards of loud music are quite immediate, whereas the harmful effects may become visible only after years (

Blesser, 2007). The enjoyment of loud sound, moreover, appears to depend on a complex and powerful interaction of forces related to cultural, interpersonal, and intrapersonal factors. As such, it can be studied by applying the Social Ecological Model that considers four levels of influence: the intrapersonal level, the interpersonal level, the community level, and the policy level, all of them pointing toward an ecology of acceptance of high-level sound (

McLeroy et al., 1988; see

Richard et al., 2011 for an overview).

The intrapersonal level refers to the individual’s own thoughts and attitudes, reflecting personal preference for style and genre, as well as personality traits, which may influence the appreciation for loud sounds, such as sensation seeking behavior and a desire for rebelliousness (

Arnett, 1994;

Lozon and Bensimon, 2014). Loud music, in that case, is valued as providing intense stimulation and arousal. It has an exciting and arousing effect through stimulation of brainstem mechanisms, with connections to the reticular formation, which modulates our experience of sound and which may be expected to contribute to pleasurably heightened arousal (

Juslin and Västfjäll, 2008). The interpersonal level refers to the direct influence of other associated people. It describes the influence of sound on interactions with others, reflecting the desire for group membership by adopting common styles and tastes (

Bennett, 1999). The community levelconcerns the cultural influences on listener’s behavior. It refers to the accepted practices around loud music, such as the expectation of loudness from both nightclub staff and clubbers. Staff members, in particular, use loud music to market themselves in line with the conceptualization of a culture of loud sound and to influence their customers. Clubbers, as a matter of fact, seem to accept these loudness levels, even when they are experienced as being too loud. Levels of around 97 dBA Leq are not uncommon (

Beach et al., 2013), mostly starting at a level of 85 dBA Leq but rising gradually through the course of the evening to reach this maximum level around midnight. The underlying mechanism is adaptation as the auditory system is highly adaptive to high-level sound, with physiological adaptation occurring at multiple sites in the cochlea (

Fettiplace and Kim, 2014) and also in the cortex (

Whitmire and Stanley, 2016). As such, sound levels are raising in order to meet what club managers consider to be the wishes of the customers who perceive loudness as a function of both the external level of sound and the degree of physiological adaptation. The policy level, finally, deals with the influence of legal requirements and aspects of government policy concerning noise levels in the workplace (

McLeroy et al., 1988; see also

Welch and Fremaux, 2017a,

b). The Social Ecological Model, moreover, claims that influences toward good health should be present at each of the levels of the model in order to guarantee good health behavior.

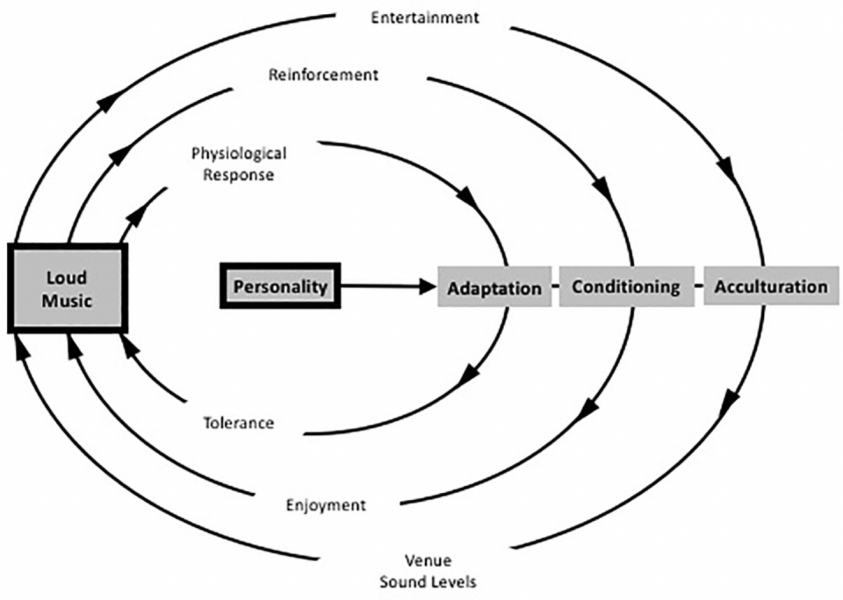

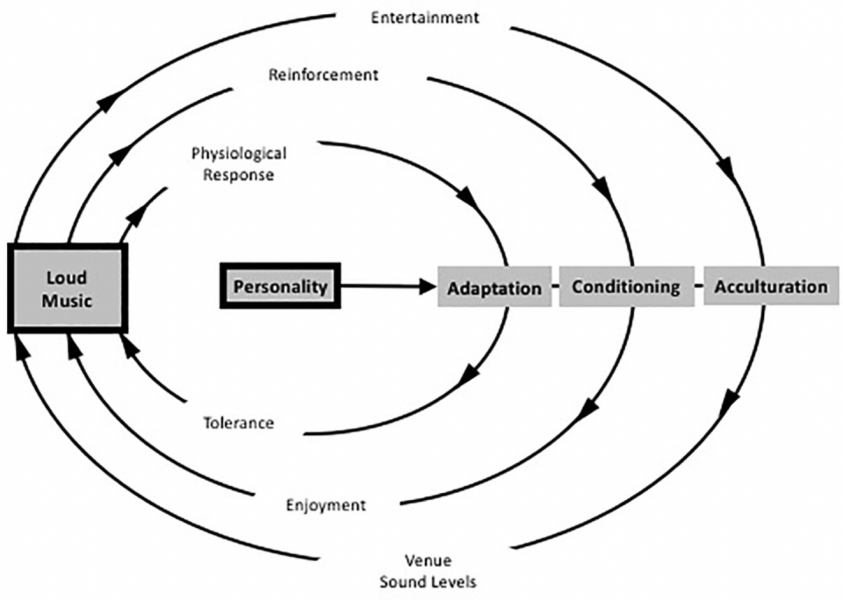

A related theory has been proposed by Welch and Fremaux: the CAALM model, which is short for Conditioning, Adaptation, and Acculturation to Loud Music (

Welch and Fremaux, 2017a,

b). It is based on three processes: (1) an initial adaptation that should enable listeners to overcome the experienced discomfort that is associated with loud music; (2) a classically conditioned response that repeatedly pairs levels of loudness with perceived benefits of loudness such as masking of other unwanted sound, social benefits, arousal, excitement, and other associated benefits such as dancing, fun, friends, alcohol, or other substances, and (3) an acculturation process wherein large groups of listeners start to perceive loud music as the norm and as the common association of fun (see

Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. Schematic diagram of the CAALM Model diagram showing the three parallel cycles that may lead to people enjoying loud music, and the role of personality as a moderating factor. (Figure adapted and republished with permission of Thieme Publishers from

Welch and Fremaux, 2017a).

Underlying the model are several positive features of loud sound that contribute to the conditioning effect: (1) loud music masks unwanted sounds, (2) it enables more and greater socialization (cf.

Cusick, 2006), (3) it provides opportunities for intimacy in crowded space, (4) it masks unpleasant thoughts, (5) it is arousing, and (6) it emphasizes personal identity, especially personal toughness and masculinity. The latter reflects culturally accepted norms of masculinity as being associated with activity and danger and may represent the neural interaction where a natural fear response would occur to the loud sound and then the person is able to exert control over that response, thus generating a feeling of strength (

Welch and Fremaux, 2017b).

Whoops… more words than expected… last bit coming…