The first and most famous question asked about Carnegie Hall is “how do you get there?” The origin of the similarly famous answer “practice, practice, practice” is often incorrectly attributed to Jack Bennie. However, the credit really belongs to the violinist Mischa Elman who, after completing a rehearsal that didn’t please him, was leaving Carnegie Hall by the backstage entrance when he as was approached by two tourists looking for the hall’s main entrance. Seeing his violin case, they asked, “How do you get to Carnegie Hall?” Without looking up and continuing on his way, Elman simply replied, “practice.”

The second question that is often asked about Carnegie, is why it enjoys a reputation as being one of the finest sounding concert halls in the world? What makes the acoustics of Carnegie Hall so special, and so different from other halls? Carnegie Hall’s architect William Burnett Tuthill, an amateur cellist, studied European concert halls famous for their acoustics, and consulted with architect Dankmar Adler, of the Chicago firm Adler and Sullivan, a noted acoustical authority before constructing the hall in 1891. Drawing on his findings (and in some cases his own intuition), he eliminated common theatrical features like heavy curtains, frescoed walls, and chandeliers that could impair good sound distribution. Carnegie Hall’s smooth interior, elliptical shape, slightly extended stage, and domed ceiling help project soft and loud tones alike to any location in the hall with equal clarity and richness.

That said, the question that most concert goers (and especially audiophiles) might want to know is simply, where in the hall is the best sound? Where should one sit for the best sound? Since moving from DFW to NJ 3 years ago, I have spent many wonderful evenings attending concerts at Carnegie with the specific intent of trying to answer that very question.

Many long-time Carnegie stalwarts are adamant that the best sound is, perhaps surprisingly, in the balcony. That’s right. The cheap seats; the peanut gallery! Yet for the past few years I have resisted sitting there because I simply couldn’t believe the sound would be as good as some of the far more prestigious seats such as the First or Second Tier or Dress Circle. And so the quest began.

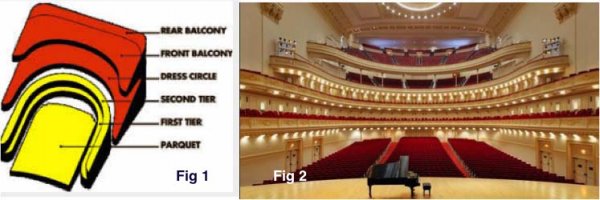

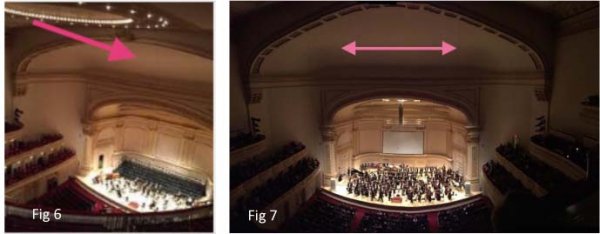

The first thing that was unequivocal and clear, is that like most of the concert halls I have been in, seats on the Orchestra (Parquet- see Fig. 1,2) floor are invariably disappointing. How can they not be? For the most part, your ears are at a level that is about on par with the symphony performer’s shoes, or even lower, unless you are in very rear of the Parquet seating. Even if the orchestra uses risers to elevate the rear sections of the orchestra, for the most part, you are not getting any direct access to the sound coming from the sonic mouths of most of the instruments, whether it be the resonant front surfaces of the stringed instruments, the bell of the woodwinds or horns, or the drum heads or surfaces of the percussion. (Some notable exceptions exist, such as the remarkable hall of the Berlin Philharmonic, in which the orchestra seats rise gradually from the floor on which the musicians sit.)

Moving upwards (towards the top of) the Hall, the First Tier and Second tier (Fig. 3) are quite good sounding, as one might expect. Yet there are some surprising differences, depending on the exact seat. For the most part, I prefer to sit in the center, but I have on occasion sat further forward and more on the side of the horseshoes of the First or Second tier. Once, I bought two single seats for one particular performance that consisted row 1 in box 34 (just off dead center) and row 2 in box 32 (dead center) in the Second tier and switched at intermission. These seats were no more than 5 feet apart, in adjacent boxes, yet the sound was surprisingly different! (I preferred the slightly more balanced sound in the row 2, box 32 seat as opposed the row 1, box 31 seat). But in general, there are no bad seats in the First and Second Tiers. Fig. 4 is a somewhat magnified view one would see from the Second Tier center seats.

The Dress circle is a mixed bag. The front of the Dress Circle is very good. By that I specifically refer to the first 2 rows only. Once you get beyond that, the sound quality diminishes because of the balcony overhang that is above the rear Dress Circle seats.

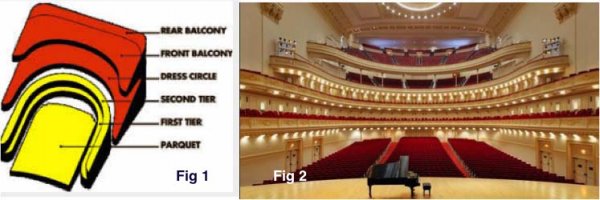

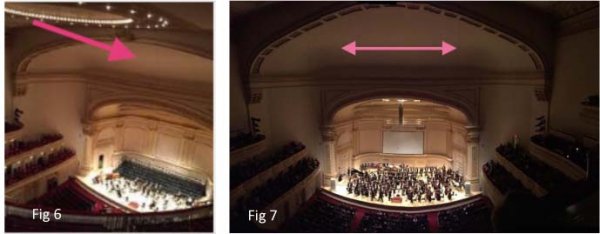

But to cut right to the chase, I was unprepared for the sound that I heard from the front of the balcony. I attended Marin Alsop and the Baltimore Symphony performing Mahler’s 5th a few months ago and the sound was just spectacular. It was full, lush, balanced, detailed, powerful and just flat out magnificent. (Did I mention powerful!) It really is the finest sound in the hall. Fig 5 is the view I had from the front of the balcony looking down upon the orchestra. But it does not reveal what I think is the secret of the hall’s sound from the balcony. Fig. 6 and 7 reveal a huge full hall width frontal arch, well above the stage and just below the ceiling, that I believe is the key to the superb sound in the balcony.

While sitting in the front section of the balcony, if you close your eyes and are asked to point to the source of the music, you will not point to the stage, but surprisingly, to the region that is smack dab middle of that high dramatic arch at the top of the hall (pink arrow). The arch is situated such that it is directly in front of the balcony seats but it is this locus from which most of the sound arises. The best analogy I can provide is this. Have you ever been to one of those places that there are parabolic reflectors whereby someone can whisper something in front of one of them and the listener in front of the second one a long distance away, can hear every word clearly? There is a famous example in the Capital building in Washington DC where it is said that many years ago, until is was discovered, opposing political parties could “steal’ secrets from the other party whispering in front of the parabolic ceiling arches at the other end of the room. There is also a nice set of parabolic arches that entertains kids and other passers-by on Market Street near 5th St. in San Francisco. You get the idea. The wide frontal ceiling arch located directly in front of the balcony seats at Carnegie seems to accomplish the same sonic feat. There is no detail of the music coming from the stage that escapes the arch as the sound is conveyed to the balcony seats. As I said, you are looking down at the stage, but the music is seemingly coming from directly in front of you as if by magic. And the result is just incredible.

A few pertinent comments. Most audiophiles are, for lack of a better term, imaging whores. We love it when we can say that we have systems whereby the sonic soundstage is laid out in such detail and precision, that you can tell whether of not it was the second violinist in the first row of the string section who farted, or whether the sound came from the first violinist in the second row. Well, to some degree you might be able to make that distinction when you are sitting in the Parquet, and even to some degree from the First and Second Tier. But surprisingly, that’s not what you will hear from the balcony seats. Rather you hear an incredible nearly homogeneous sound field of music that washes over you without many of the sonic localization clues you would consider de riguer when listening to a first class home stereo system. And the sound just takes your breath away. In fact, once you hear it, to be honest, you won’t give a flying you know what, that the separation and spatial representation of what you typically think of as being “concert hall” sound, is very different in the real world of the balcony seats at Carnegie. In many ways, this was the finest concert hall sound I have heard, and I’ve been to a lot of halls both in the US and in Europe. Close seconds are my old first row box M season tickets in the Grand Tier of Powell Hall in St. Louis, and some wonderful seats in Section A at the Berlin Philharmonic. But the balcony seats at Carnegie probably eclipses them all for pure sound.

One or two additional comments are in order. I can appreciate that the average height of human males in the 17th and 18th centuries was about 5’5”. So who needed a lot of legroom for them? But by the time the Hall was built in 1891, this increased to about 5’7”. And there is no shortage of 6’ men alive today. Yet, it seems inconceivable to me that anyone would purposely design a concert hall in 1891 that functions as a torture test for seating tall men for two hours, as did the imbeciles who designed the balcony seating of Carnegie Hall.

Here’s what its like to sit in the second row of the balcony. Take a look at this poor bastard in the green slacks who is forced to sit with his knees basically immobile for the entire performance (Fig. 8-9). I presume he finally got some circulation in his legs at intermission because he came back for more, as did I, but it wasn’t fun. I can tell you that.

You can easily see that his knees actually overhang the back of the seat in front of him. Can you imagine what the poor patron in front him might be thinking if the guy didn’t shower that day? In fact, I’ll bet you that in some states, two people sitting with their head and genitalia that close without mutual consent is probably against the law. Check my last picture which tells the story best (Fig 10)

As near as I can tell there is about 7-8 inches between your front seat cushion to the back of the chair in front of you. What the hell were those seat planners thinking? Honestly, it is inexcusable and unfortunately, if you are tall, it detracts greatly from the overall experience of attending a performance at Carnegie in the balcony seats that have the best sound. I know that the seat spacing elsewhere in the Hall, while not exactly luxurious, is not nearly as onerous as the balcony seats. Quite a paradox. Did the hall designers actually say "Give the people in the cheap seats the best sound but the least comfort"? Hmmm....

I’ll close by commenting that the performance I heard that night from the balcony was particularly poignant because it was around the time that the next conductor of the NY Philharmonic was announced. Although Marin Alsop was apparently a finalist, and had a lot of folks rooting for her because Leonard Bernstein was her mentor as well as other well-deserved reasons, she did not get the post. (She also happens to be a damned good Mahlerite and that evening’s performance featured a fantastic rendering of Mahler’s 5th). Rather, Jaap Von Zweden will be the NY Phil’s music director beginning in 2018. I was fortunate to watch him lead the Dallas Symphony Orchestra for 8 years while living there before moving back to NJ, and I think his appointment is a great one. (IMHO, his Mahler in particular, is outstanding!) So I will be busy running back and forth between Carnegie and David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center with two orchestral series subscriptions for quite a while. It really is a privilege to have access to both a superb hometown band playing regularly at Lincoln Center, as well as the opportunity to see many of the world’s greatest orchestras and conductors who come through Carnegie on a regular basis. Now if Carnegie could only provide some balcony seats that would allow some lower body circulation so I can come in as a baritone but not leave as a soprano, life would be near perfect.

The second question that is often asked about Carnegie, is why it enjoys a reputation as being one of the finest sounding concert halls in the world? What makes the acoustics of Carnegie Hall so special, and so different from other halls? Carnegie Hall’s architect William Burnett Tuthill, an amateur cellist, studied European concert halls famous for their acoustics, and consulted with architect Dankmar Adler, of the Chicago firm Adler and Sullivan, a noted acoustical authority before constructing the hall in 1891. Drawing on his findings (and in some cases his own intuition), he eliminated common theatrical features like heavy curtains, frescoed walls, and chandeliers that could impair good sound distribution. Carnegie Hall’s smooth interior, elliptical shape, slightly extended stage, and domed ceiling help project soft and loud tones alike to any location in the hall with equal clarity and richness.

That said, the question that most concert goers (and especially audiophiles) might want to know is simply, where in the hall is the best sound? Where should one sit for the best sound? Since moving from DFW to NJ 3 years ago, I have spent many wonderful evenings attending concerts at Carnegie with the specific intent of trying to answer that very question.

Many long-time Carnegie stalwarts are adamant that the best sound is, perhaps surprisingly, in the balcony. That’s right. The cheap seats; the peanut gallery! Yet for the past few years I have resisted sitting there because I simply couldn’t believe the sound would be as good as some of the far more prestigious seats such as the First or Second Tier or Dress Circle. And so the quest began.

The first thing that was unequivocal and clear, is that like most of the concert halls I have been in, seats on the Orchestra (Parquet- see Fig. 1,2) floor are invariably disappointing. How can they not be? For the most part, your ears are at a level that is about on par with the symphony performer’s shoes, or even lower, unless you are in very rear of the Parquet seating. Even if the orchestra uses risers to elevate the rear sections of the orchestra, for the most part, you are not getting any direct access to the sound coming from the sonic mouths of most of the instruments, whether it be the resonant front surfaces of the stringed instruments, the bell of the woodwinds or horns, or the drum heads or surfaces of the percussion. (Some notable exceptions exist, such as the remarkable hall of the Berlin Philharmonic, in which the orchestra seats rise gradually from the floor on which the musicians sit.)

Moving upwards (towards the top of) the Hall, the First Tier and Second tier (Fig. 3) are quite good sounding, as one might expect. Yet there are some surprising differences, depending on the exact seat. For the most part, I prefer to sit in the center, but I have on occasion sat further forward and more on the side of the horseshoes of the First or Second tier. Once, I bought two single seats for one particular performance that consisted row 1 in box 34 (just off dead center) and row 2 in box 32 (dead center) in the Second tier and switched at intermission. These seats were no more than 5 feet apart, in adjacent boxes, yet the sound was surprisingly different! (I preferred the slightly more balanced sound in the row 2, box 32 seat as opposed the row 1, box 31 seat). But in general, there are no bad seats in the First and Second Tiers. Fig. 4 is a somewhat magnified view one would see from the Second Tier center seats.

The Dress circle is a mixed bag. The front of the Dress Circle is very good. By that I specifically refer to the first 2 rows only. Once you get beyond that, the sound quality diminishes because of the balcony overhang that is above the rear Dress Circle seats.

But to cut right to the chase, I was unprepared for the sound that I heard from the front of the balcony. I attended Marin Alsop and the Baltimore Symphony performing Mahler’s 5th a few months ago and the sound was just spectacular. It was full, lush, balanced, detailed, powerful and just flat out magnificent. (Did I mention powerful!) It really is the finest sound in the hall. Fig 5 is the view I had from the front of the balcony looking down upon the orchestra. But it does not reveal what I think is the secret of the hall’s sound from the balcony. Fig. 6 and 7 reveal a huge full hall width frontal arch, well above the stage and just below the ceiling, that I believe is the key to the superb sound in the balcony.

While sitting in the front section of the balcony, if you close your eyes and are asked to point to the source of the music, you will not point to the stage, but surprisingly, to the region that is smack dab middle of that high dramatic arch at the top of the hall (pink arrow). The arch is situated such that it is directly in front of the balcony seats but it is this locus from which most of the sound arises. The best analogy I can provide is this. Have you ever been to one of those places that there are parabolic reflectors whereby someone can whisper something in front of one of them and the listener in front of the second one a long distance away, can hear every word clearly? There is a famous example in the Capital building in Washington DC where it is said that many years ago, until is was discovered, opposing political parties could “steal’ secrets from the other party whispering in front of the parabolic ceiling arches at the other end of the room. There is also a nice set of parabolic arches that entertains kids and other passers-by on Market Street near 5th St. in San Francisco. You get the idea. The wide frontal ceiling arch located directly in front of the balcony seats at Carnegie seems to accomplish the same sonic feat. There is no detail of the music coming from the stage that escapes the arch as the sound is conveyed to the balcony seats. As I said, you are looking down at the stage, but the music is seemingly coming from directly in front of you as if by magic. And the result is just incredible.

A few pertinent comments. Most audiophiles are, for lack of a better term, imaging whores. We love it when we can say that we have systems whereby the sonic soundstage is laid out in such detail and precision, that you can tell whether of not it was the second violinist in the first row of the string section who farted, or whether the sound came from the first violinist in the second row. Well, to some degree you might be able to make that distinction when you are sitting in the Parquet, and even to some degree from the First and Second Tier. But surprisingly, that’s not what you will hear from the balcony seats. Rather you hear an incredible nearly homogeneous sound field of music that washes over you without many of the sonic localization clues you would consider de riguer when listening to a first class home stereo system. And the sound just takes your breath away. In fact, once you hear it, to be honest, you won’t give a flying you know what, that the separation and spatial representation of what you typically think of as being “concert hall” sound, is very different in the real world of the balcony seats at Carnegie. In many ways, this was the finest concert hall sound I have heard, and I’ve been to a lot of halls both in the US and in Europe. Close seconds are my old first row box M season tickets in the Grand Tier of Powell Hall in St. Louis, and some wonderful seats in Section A at the Berlin Philharmonic. But the balcony seats at Carnegie probably eclipses them all for pure sound.

One or two additional comments are in order. I can appreciate that the average height of human males in the 17th and 18th centuries was about 5’5”. So who needed a lot of legroom for them? But by the time the Hall was built in 1891, this increased to about 5’7”. And there is no shortage of 6’ men alive today. Yet, it seems inconceivable to me that anyone would purposely design a concert hall in 1891 that functions as a torture test for seating tall men for two hours, as did the imbeciles who designed the balcony seating of Carnegie Hall.

Here’s what its like to sit in the second row of the balcony. Take a look at this poor bastard in the green slacks who is forced to sit with his knees basically immobile for the entire performance (Fig. 8-9). I presume he finally got some circulation in his legs at intermission because he came back for more, as did I, but it wasn’t fun. I can tell you that.

You can easily see that his knees actually overhang the back of the seat in front of him. Can you imagine what the poor patron in front him might be thinking if the guy didn’t shower that day? In fact, I’ll bet you that in some states, two people sitting with their head and genitalia that close without mutual consent is probably against the law. Check my last picture which tells the story best (Fig 10)

As near as I can tell there is about 7-8 inches between your front seat cushion to the back of the chair in front of you. What the hell were those seat planners thinking? Honestly, it is inexcusable and unfortunately, if you are tall, it detracts greatly from the overall experience of attending a performance at Carnegie in the balcony seats that have the best sound. I know that the seat spacing elsewhere in the Hall, while not exactly luxurious, is not nearly as onerous as the balcony seats. Quite a paradox. Did the hall designers actually say "Give the people in the cheap seats the best sound but the least comfort"? Hmmm....

I’ll close by commenting that the performance I heard that night from the balcony was particularly poignant because it was around the time that the next conductor of the NY Philharmonic was announced. Although Marin Alsop was apparently a finalist, and had a lot of folks rooting for her because Leonard Bernstein was her mentor as well as other well-deserved reasons, she did not get the post. (She also happens to be a damned good Mahlerite and that evening’s performance featured a fantastic rendering of Mahler’s 5th). Rather, Jaap Von Zweden will be the NY Phil’s music director beginning in 2018. I was fortunate to watch him lead the Dallas Symphony Orchestra for 8 years while living there before moving back to NJ, and I think his appointment is a great one. (IMHO, his Mahler in particular, is outstanding!) So I will be busy running back and forth between Carnegie and David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center with two orchestral series subscriptions for quite a while. It really is a privilege to have access to both a superb hometown band playing regularly at Lincoln Center, as well as the opportunity to see many of the world’s greatest orchestras and conductors who come through Carnegie on a regular basis. Now if Carnegie could only provide some balcony seats that would allow some lower body circulation so I can come in as a baritone but not leave as a soprano, life would be near perfect.

Last edited: