The 12 Transcendental Etudes discussed below comprise the 1st disc of this 2 CD set. Incredible playing by one of today's extraordinary pianists. (The legendary pianist Georges Cziffra also recorded these in mono in the late fifties but most audiophiles will prefer the current DGG recording.)

Studies in Reckless Virtuosity

Franz Liszt’s ‘Transcendental Etudes’ underwent many revisions, emerging as supremely challenging pieces filled with sonorous splendor.

Studies in Reckless Virtuosity

Franz Liszt’s ‘Transcendental Etudes’ underwent many revisions, emerging as supremely challenging pieces filled with sonorous splendor.

By

David Dubal

Nov. 16, 2018 12:20 p.m. ET

By the first years of the 19th century, the piano had become the major domestic musical instrument. Composers began turning out countless études (studies), short pieces of music designed to help student pianists achieve technical competence in scales, arpeggios, octaves, trills and so forth.

Mostly, these concoctions were musically arid and unmemorable. Carl Czerny (1791-1857), Beethoven’s prize pupil, was king of the étude, profitably churning out such pieces. They are helpful, but in their medicinal content they have been practiced grudgingly throughout the generations. H.L. Mencken, a lifelong amateur pianist, wrote, “As late as 1930, being in Vienna, I desecrated Czerny’s grave.”

In 1826, Franz Liszt (1811-1886), who had studied with Czerny, composed a dozen études in his teacher’s manner, but with a difference. Each of them possesses a vital musical kernel. These early works are seldom practiced by anyone today, but one may listen to them on a Naxos CD played by William Wolfram.

Over the course of the next decade Liszt consolidated his unparalleled prowess as a pianist. However, he remained haunted by his early études, and in 1839 the mature composer rewrote them, giving them unheard of technical difficulties, calling them “Twelve Grandes Etudes.” In a review, Robert Schumann called them “true storm and terror etudes.…Weaker executants will only excite laughter by attempting them.”

The fact is, Liszt gave birth to a monster, and the second set is the most difficult and muscular pianistic creation of the time. Liszt had put himself into a technical void and although he performed them with dazzling success, he hated the fact that other pianists would shun them.

Thirteen long years elapsed. Liszt had retired from the concert stage at age 36 and now lived in Weimar as court composer and conductor. He was at the dawn of his legendary teaching career. In 1851 he revised and entirely reworked his études, eliminating the dross while retaining their daring virtuosity, and adding to their sonorous splendor and romantic allure. While still among the most difficult works in the repertoire, the third version achieved a magnificent playability. For all but two he added an evocative title, now calling the cycle “Etudes d’exécution transcendante.”

A comparison of the three versions reveals an extraordinary evolution from 1826 to 1851. Here we are shown dramatically Liszt’s genius for pianistic crystallization. The third version adds a new dimension to piano writing, and the “Transcendental Etudes” remain one of the masterly cycles of the Romantic piano literature. Always magnanimous, Liszt dedicated them to Czerny, “to whom I owe everything.”

Briefly, let’s describe them.

No. 1, Preludio, is a mere 40 bars, a flash of lightning that dares the player to begin the 75-minute journey.

No. 2 is without title, a whirlwind seemingly inspired by the infernal violinist Niccolò Paganini.

No. 3, Paysage (Landscape), is a lovely pastoral, a study in legato and various textures; later, human passion breaks through the bucolic atmosphere.

No. 4, Mazeppa, is a startlingly graphic six minutes, inspired by Victor Hugo’s poem of the same name. This maelstrom is an exhausting workout for wrist and arms.

No. 5, Feux Follets (Will-o’-the-wisp), is one of the finest double-note études in the piano literature, shimmering with colored broken glass splintering in thin air. Its difficulties are heartbreaking.

No. 6, Vision, a work of impressive pomp, is a powerful chordal study within sweeping arpeggiations.

No. 7, Eroica, is my least favorite musically, less heroic than grandiose.

No. 8, Wilde Jagd (Wild Hunt), is a colossal explosion, painting the proverbial German nocturnal hunt. Hearing it, I think of Lao Tzu’s words, “riding and hunting makes my mind go wild with excitement.”

No. 9, Ricordanza (Remembrance), is an almost excruciating piece of nostalgia, with richly ardent ornamentation. The composer and pianist Ferruccio Busoni likened it to a packet of yellowed love letters.

No. 10 is without title. The tempo marking is

allegro agitato molto, feverishly breathless; at one moment, Liszt writes in the score “

disperato.” The left hand must overcome treacherous pitfalls.

No. 11, Harmonies du Soir (Evening Harmonies), is nearly 10 minutes of ecstatic, luxuriant lyricism, perfumes of a summer evening, from evanescent impressionist textures to massive chords.

No. 12, Chasse-Neige (Snowscape), a sobbing melody with tremolando accompaniments in the right hand, is a fatal picture of Romantic desolation as snow envelops the earth, the wind moaning in tragic chromatic scales.

In his memoir “Life and Liszt,” one of the composer’s finest pupils, Arthur Friedheim, noted that “Liszt sensed the spiritual, could see and hear things and sounds beyond the ken. He had the intuition, the mystic power, to generate beyond the empyrean.”

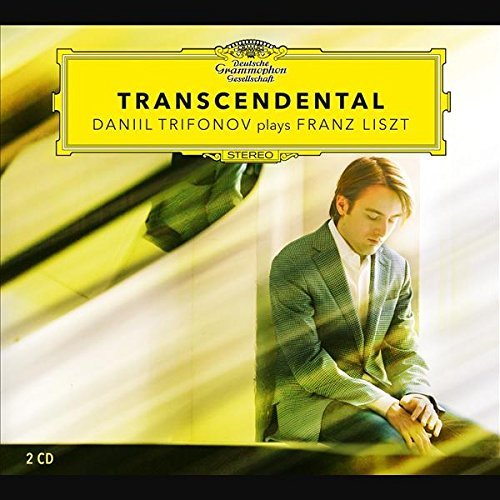

There are few pianists who can do justice to each of the final versions of the “Transcendental Etudes,” but recordings by György Cziffra (EMI) and

Daniil Trifonov (Deutsche Grammophon) offer two admirable, searching interpretations of the cycle. For any pianist, studying these challenging compositions will benefit everything else that they play.

—Mr. Dubal is the author of “The Art of the Piano.” His “Reflections From the Keyboard” can be heard every week on WQXR.