My listening to jazz coincided with my discovery of the joy of listening to vinyl in mono. Once you hear a great mono record on a true mono cartridge — such as the great Miyajima Zero Infinity — there’s no going back. Stereo seems such a letdown. The very best source in my house is a fully restored Garrard 301 turntable with a 12” SME mounted with the Miyajima. You can keep your stereo. Mono vinyl is so breathtakingly real and vibrant. It’s the closest I’ve heard to live music in my 35+ years of being an audiophile. My fancy Lampizator Pacific seems such a letdown in comparison ??

View attachment 111745

View attachment 111746

Very cool, must sound great.

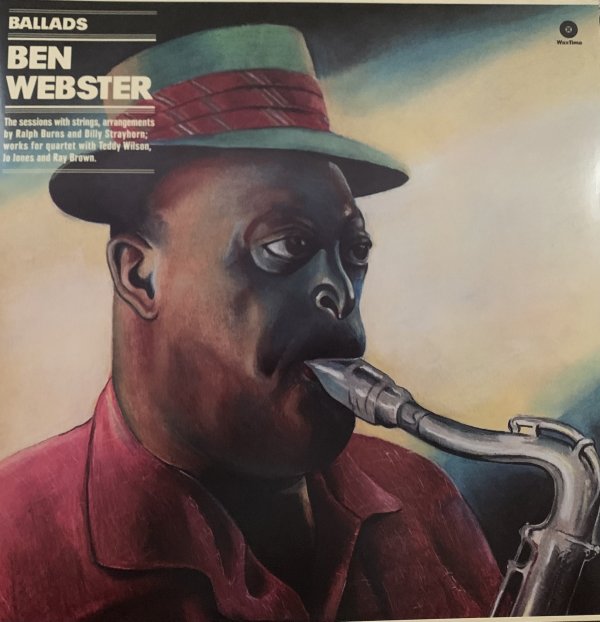

That Ben Webster album contains several lovely sessions with strings recorded in 1954 and 1955. The last four tracks are a quartet session recorded in 1954 with Teddy Wilson on piano, Ray Brown on bass, and Jo Jones on drums. For everyone's benefit, here is an outstanding track from that session:

Available on Qobuz in several releases, including this one:

https://open.qobuz.com/track/4350165

The Internet Archive contains different versions of those albums, and you can read the liner notes:

https://archive.org/details/cd_music-for-loving-ben-webster-with-strings_ben-webster

Here is a portrait of Webster by Loren Schoenberg:

In the first part, Schoenberg shows a video of the "Sound of Jazz" show, in which you have an all-star cast: Webster, Hawkins, Lester Young, Gerry Mulligan, Roy Eldridge, Vic Dickenson, Doc Cheatham, accompanying Billie Holiday. A rare opportunity to compare the styles on tenor of Young, Webster and Hawkins at the time:

Enjoy the videos and music you love, upload original content, and share it all with friends, family, and the world on YouTube.

www.youtube.com

It is nice to see how Billie Holiday reacts so sympathetically to the different soloists. Look at the young Gerry Mulligan smiling as he watches Coleman Hawkins.

In his book "Early Jazz", Gunther Schuller writes about Lester Young's performance that day:

"I cannot, of course, pretend to know intimately all the live performing of Lester’s final years; and perhaps amidst the pitifully groping, floundering attempts to somehow keep going, there were moments when the light of Lester’s art again shone brightly. I do know that one such moment occurred on the December 1957 telecast The Sound of Jazz, unquestionably the finest hour jazz has ever had on television. How fortunate we are that one of Lester’s final and most glorious moments was thus captured on electronic media: his heart-rending twelve bars on Fine and Mellow. Whitney Balliett and Nat Hentoff, co-producers of the program, have both spoken eloquently of Lester’s sad condition during the rehearsals and performance. Lester was so totally remote and uncommunicative, as well as physically incapacitated, that at one point it was thought necessary to cut him out of the show altogether. But that seemed too cruel, so it was finally decided to limit his involvement to one chorus on Billie Holiday’s slow blues, Fine and Mellow, in the hope that she, his long-time friend, would provide the one possible stimulus for a reasonable musical participation.

The document of that television show demonstrates the triumph of soul over matter. For Lester, so sick that he could hardly stand, barely able to draw enough breath to sustain even a short phrase, nonetheless rose to the occasion and played a canticle of such overwhelming expressiveness as to put all the other playing into distant perspective. I think that Lester was dimly yet deeply aware of the fact that even some of his best friends and colleagues in the studio had given up on him. But he was to teach them all a lesson— a lesson particularly in economy and what he meant by “telling a story.” In his twelve halting, recitative-like bars he played a bare forty-five notes (not counting another eighteen embellishmental or passing tones), this about half of Webster’s majestic and ornate solo and one-third of Gerry Mulligan’s double-time chorus. This was, of course, not some statistical game to see who could play the fewest notes. But Lester showed them, and showed for all times— as he had so often done in the past— that sometimes one single deeply expressed note could say more than a hundred skillfully executed others. Lester was undoubtedly also expressing his feelings for Billie— perhaps he sensed it would be his last chance to do so— and kept his solo, like her singing, pared-down to essentials."

I read somewhere else that his solo brought the recording engineers to tears...