The WBF humor and joke thread.

- Thread starter treitz3

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

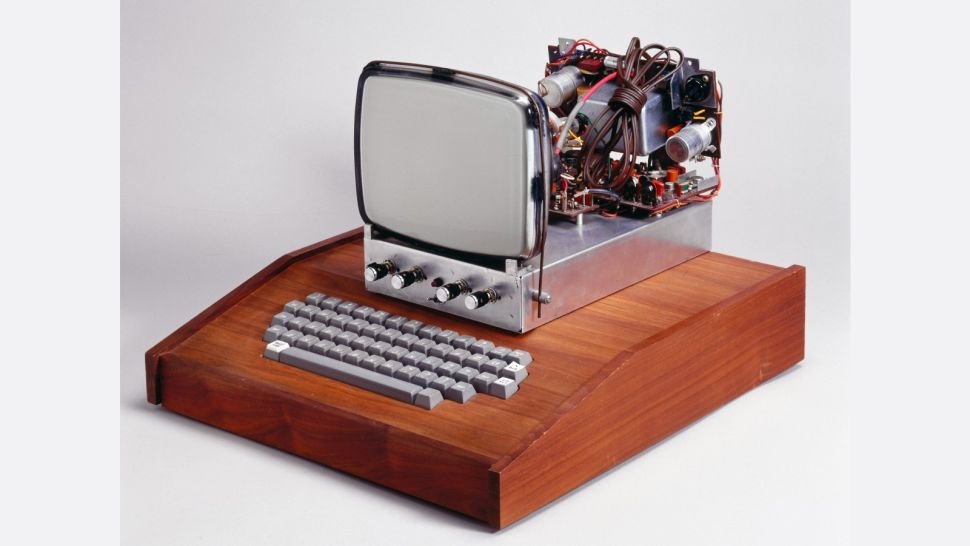

It needs an abacus to the right of the keyboard for calculating and crunching numbers . . . maybe that was on Mac 1.0

Last edited:

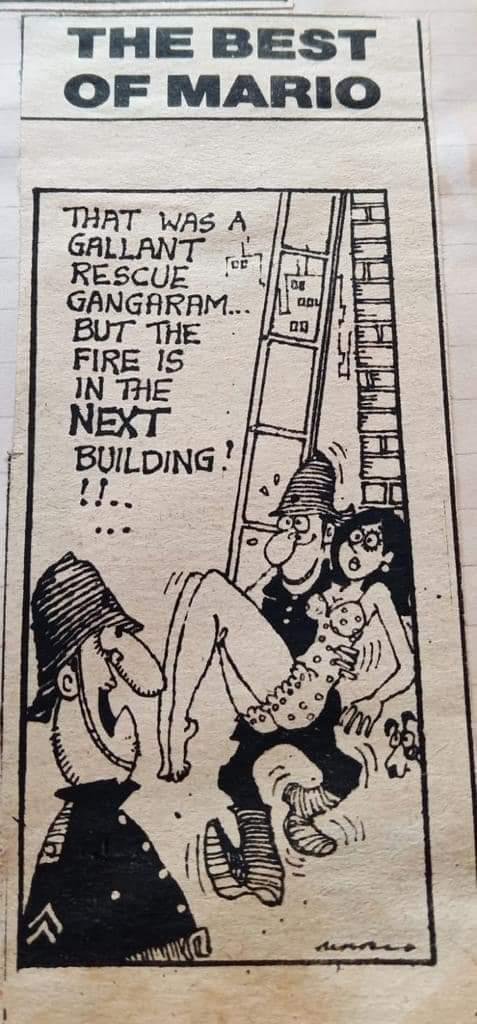

When der is something

New and exciting to zee

It's nice to have a Showgirl

To show it to Me !

View attachment 87901

Wrong movie. This one calls for Hungarian accent.

https://longkft.hu/audioblog/orion-hangsugarzok/

Let face it ! nobody wants a Hung garian if your tired . . .

Francis Bacon was an influential statesman, philosopher, writer, and scientist in the sixteenth century. He died while stuffing snow into a chicken. He had been struck by the notion that snow instead of salt might be used to preserve meat. To test his theory he stood outside in the snow and attempted to stuff the bird. The chicken didn't freeze, but Bacon did, prompting the question "Which froze first? The Bacon or the egg?"

On June 28, 2009, Stephen Hawking hosted a party for time travelers, but he sent out the invitations only afterward.

No one turned up.

He offered this as experimental evidence that time travel is not possible.

“I sat there a long time,” he said, “but no one came.”

No one turned up.

He offered this as experimental evidence that time travel is not possible.

“I sat there a long time,” he said, “but no one came.”

An atheist, a vegan, and a crossfitter walk into a bar. I only know this because they told everyone in two minutes

Last edited:

A family was having dinner once when the youngest boy asked his father whether worms tasted nice when we eat them. Both the parents reprimanded the little boy and told him that these things shouldn't be discussed over the dinner table. When the father asked the boy after dinner why he had asked such a question, he replied, "Papa, I think worms taste okay because there was one in your noodles."

During the Civil War, the U.S. Treasury received a check for $1,500 from a private citizen who said he had misappropriated government funds while serving as a quartermaster in the Army. He said he felt guilty.

“Suppose we call this a contribution to the conscience fund and get it announced in the newspapers,” suggested Treasury Secretary Francis Spinner. “Perhaps we will get some more.”

Ever since, then the Treasury has maintained a “conscience fund” to which guilt-ridden citizens can contribute. In its first 20 years, the fund received $250,000; by 1987 it had taken in more than $5.7 million. One Massachusetts man contributed 9 cents for using a damaged stamp on a letter, but in 1950 a single individual sent $139,000.

In order to encourage citizens to contribute, Treasury officials don’t try to identify or punish the donors. Most donations are anonymous, and many letters are from clergy, following up confessions taken at deathbeds.

Many contributions are sent by citizens who have resolved to start anew in life by righting past wrongs, but some are more grudging. In 2004, one donor wrote, “Dear Internal Revenue Service, I have not been able to sleep at night because I cheated on last year’s income tax. Enclosed find a cashier’s check for $1,000. If I still can’t sleep, I’ll send you the balance.”

“Suppose we call this a contribution to the conscience fund and get it announced in the newspapers,” suggested Treasury Secretary Francis Spinner. “Perhaps we will get some more.”

Ever since, then the Treasury has maintained a “conscience fund” to which guilt-ridden citizens can contribute. In its first 20 years, the fund received $250,000; by 1987 it had taken in more than $5.7 million. One Massachusetts man contributed 9 cents for using a damaged stamp on a letter, but in 1950 a single individual sent $139,000.

In order to encourage citizens to contribute, Treasury officials don’t try to identify or punish the donors. Most donations are anonymous, and many letters are from clergy, following up confessions taken at deathbeds.

Many contributions are sent by citizens who have resolved to start anew in life by righting past wrongs, but some are more grudging. In 2004, one donor wrote, “Dear Internal Revenue Service, I have not been able to sleep at night because I cheated on last year’s income tax. Enclosed find a cashier’s check for $1,000. If I still can’t sleep, I’ll send you the balance.”

Clearing conscience. Good for them. It is never too late.During the Civil War, the U.S. Treasury received a check for $1,500 from a private citizen who said he had misappropriated government funds while serving as a quartermaster in the Army. He said he felt guilty.

“Suppose we call this a contribution to the conscience fund and get it announced in the newspapers,” suggested Treasury Secretary Francis Spinner. “Perhaps we will get some more.”

Ever since, then the Treasury has maintained a “conscience fund” to which guilt-ridden citizens can contribute. In its first 20 years, the fund received $250,000; by 1987 it had taken in more than $5.7 million. One Massachusetts man contributed 9 cents for using a damaged stamp on a letter, but in 1950 a single individual sent $139,000.

In order to encourage citizens to contribute, Treasury officials don’t try to identify or punish the donors. Most donations are anonymous, and many letters are from clergy, following up confessions taken at deathbeds.

Many contributions are sent by citizens who have resolved to start anew in life by righting past wrongs, but some are more grudging. In 2004, one donor wrote, “Dear Internal Revenue Service, I have not been able to sleep at night because I cheated on last year’s income tax. Enclosed find a cashier’s check for $1,000. If I still can’t sleep, I’ll send you the balance.”

Similar threads

- Replies

- 3

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 3

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 179

- Views

- 19K